The Object class

Table of contents

- The

Objectclass - The

toString()method - The

equals()andhashCode()methods - The

getClass()method - The

wait(),notify()andnotifyAll()methods

The Object class

All roads lead to rome and all classes inherit from the Object class.

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class Person {

}

The Person class does not use the extends keyword. By default, any class that dose not use the extends keyword, it automatically extends the Object class. The following example is equivalent to the above example.

package demo;

public class Person extends Object {

}

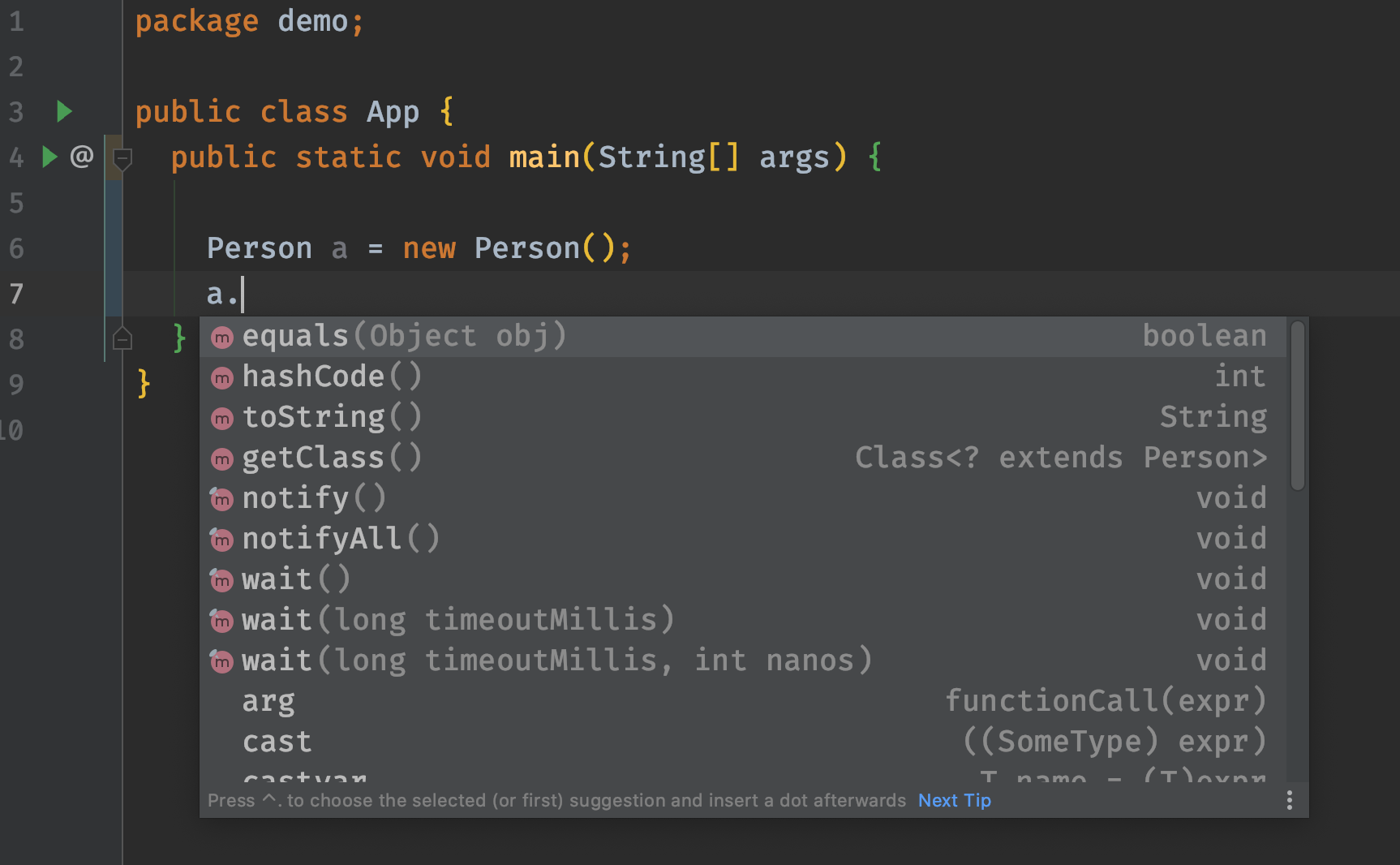

The Person class has no methods defined, yet the IDE still shows a list of methods we can use.

consider the following example.

package demo;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

public Person() {

this( null );

}

public Person( final String name ) {

this( name, null );

}

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) {

this.name = name;

this.surname = surname;

}

}

The following sections will work with the above Person class.

The toString() method

All objects in Java have a method called toString() which is used to convert an object into a programmer friendly string.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person a = new Person();

System.out.printf( "The person object: %s%n", a );

}

}

The above prints the following, meaningless, message.

The person object: demo.Person@58372a00

The toString() method is used to convert our person object into a programmer friendly string.

It is always recommended to override the toString() method and return something more useful. Item 12, Always override toString in the Effective Java book talks about the importance of overriding this method too.

package demo;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, surname=%s}", name, surname );

}

}

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person a = new Person();

final Person b = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person c = new Person( null, "Attard" );

final Person d = new Person( "Aden", "Attard" );

System.out.printf( "a = %s%n", a );

System.out.printf( "b = %s%n", b );

System.out.printf( "c = %s%n", c );

System.out.printf( "d = %s%n", d );

}

}

The above program will print the following.

a = Person{name=null, surname=null}

b = Person{name=Aden, surname=null}

c = Person{name=null, surname=Attard}

d = Person{name=Aden, surname=Attard}

The above is more useful when compared to the original message as we can see the object’s state.

Following are some important rules about the toString() method

- The

toString()method should never return anull. - Do not rely on the output of the

toString()method as a source of structured input.

Do not parse an object based on thetoString()method’s output as this may change without warning. - Do not leak sensitive information through the

toString()method.

There are cases where we may need to have a more meaningful output, such as constructing the full name from the name and surname, as shown in the following example.

package demo;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.isNullOrEmpty;

public class Person {

private String name;

private String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() {

final boolean hasName = !isNullOrEmpty( name );

final boolean hasSurname = !isNullOrEmpty( surname );

if ( hasName && hasSurname ) {

/* return name + " " + surname; */

return String.format( "%s %s", name, surname );

}

if ( hasName ) {

return name;

}

if ( hasSurname ) {

return surname;

}

return "Unknown Person!!";

}

}

The result of the toString() method depends on the state and running the previous example would now yield the following.

The person object: Unknown Person!!

The person object: Aden

The person object: Attard

The person object: Aden Attard

The above result is more appealing. While this is all good, the purpose of the toString() method is to enable the programmer to display the object’s state, in no specific format, and such output can be used in log files, for example. When an object needs to be presented in a specific manner, I prefer to have a dedicated method, such as getFullName(), instead of reusing the toString() method. In this case, each method will serve only one purpose.

package demo;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName;

import org.junit.jupiter.params.ParameterizedTest;

import org.junit.jupiter.params.converter.ConvertWith;

import org.junit.jupiter.params.provider.CsvSource;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

@DisplayName( "Person" )

public class PersonTest {

@CsvSource( {

"null,null,Unknown Person!!",

"null,Attard,Attard",

"Aden,null,Aden",

"Aden,Attard,Aden Attard"

} )

@DisplayName( "should return the full name" )

@ParameterizedTest( name = "should return {2}, when the name is {0} and surname is {1}" )

public void shouldReturnFullName(

final @ConvertWith( NullableConverter.class ) String name,

final @ConvertWith( NullableConverter.class ) String surname,

final String expectedFullName ) {

final Person subject = new Person( name, surname );

assertEquals( expectedFullName, subject.getFullName() );

}

}

We can move the contents of the toString() method to the new getFullName() method.

package demo;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.isNullOrEmpty;

public class Person {

public final String name;

public final String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

public String getFullName() {

final boolean hasName = !isNullOrEmpty( name );

final boolean hasSurname = !isNullOrEmpty( surname );

if ( hasName && hasSurname ) {

/* return name + " " + surname; */

return String.format( "%s %s", name, surname );

}

if ( hasName ) {

return name;

}

if ( hasSurname ) {

return surname;

}

return "Unknown Person!!";

}

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

Be careful with sensitive information

Unfortunately, sensitive information tends to get leaked through the toString() method. Consider the following example of a credit card.

package demo;

public class CreditCard {

private final long number;

private final int cvv;

public CreditCard( final long number, final int cvv ) {

this.number = number;

this.cvv = cvv;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "CreditCard{number=%d, cvv=%d}", number, cvv );

}

}

The object’s sensitive state is leaked through the toString() method as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final CreditCard a = new CreditCard( 1234_5678_9012_3456L, 123 );

System.out.printf( "Paying with: %s%n", a );

}

}

The above example will print the following

Paying with: CreditCard{number=1234567890123456, cvv=123}

Both the credit card number and the card verification value (cvv) are sensitive information and should not be part of the toString() method. Given the nature of this problem, as test is in order to make sure that no sensitive information is leaked through the toString() method.

Let say that only the last 4 digits of the credit card number should be part of the toString()’s method output and the cvv should be completely masked.

package demo;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse;

@DisplayName( "Credit card" )

public class CreditCardTest {

@Test

@DisplayName( "should only contain the last four digits of the credit card number and the cvv should be completely masked" )

public void shouldNotLeakSensitiveInformation() {

final CreditCard subject = new CreditCard( 1234_5678_9123_0000L, 123 );

assertFalse( subject.toString().matches( ".*[1-9]+.*" ) );

}

}

Given that only the last four digits of the credit card number are returned by the toString() method and these have the value of 0000 on purpose, the toString() method should not contain any numbers between 1 and 9 both inclusive. This makes sure that the first 12 digit of the credit card and the cvv are not part of the toString() method output.

The following example shows a better version of the toString() method.

package demo;

public class CreditCard {

private final long number;

private final int cvv;

public CreditCard( final long number, final int cvv ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() {

final long lastFourDigits = number % 10_000;

return String.format( "CreditCard{number=XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-%04d, cvv=XXX}", lastFourDigits );

}

}

Running the previous example will now print.

Paying with: CreditCard{number=XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-3456, cvv=XXX}

Be careful with recursive toString() calls

Consider the following example.

StackOverflowError!! package demo;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

private Person friend;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

public void setFriend( final Person friend ) {

this.friend = friend;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

/* ⚠️ There is a cyclic dependency which may cause a StackOverflowError!! s*/

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, surname=%s, friend=%s}", name, surname, friend );

}

}

Two persons can be friends. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person albert = new Person( "Albert", "Attard" );

final Person john = new Person( "John", "Ferry" );

/* Albert and John are friends */

albert.setFriend( john );

john.setFriend( albert );

System.out.printf( "%s%n", albert );

}

}

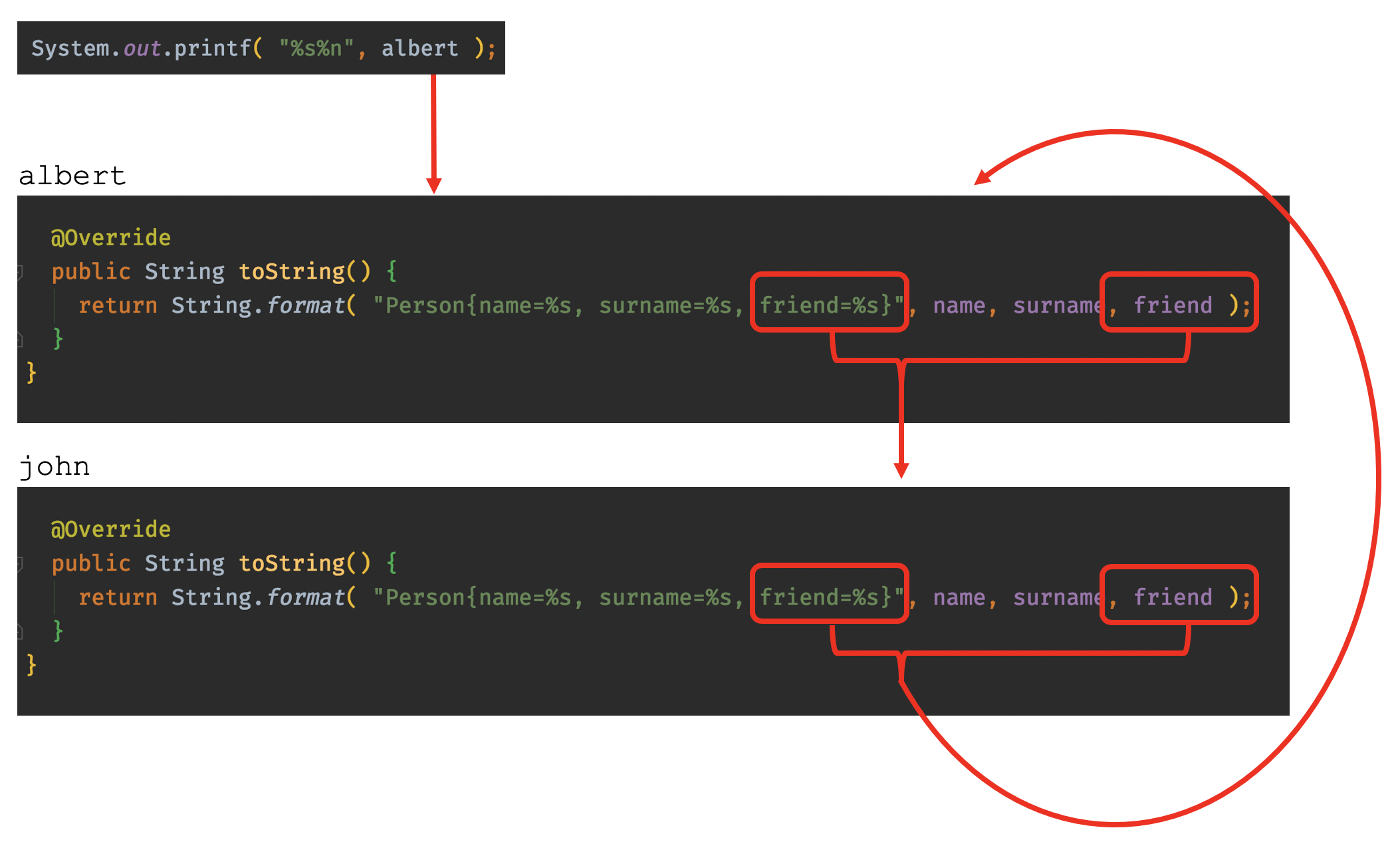

When printing variable albert, we print albert’s name and surname properties and his friend (john) using albert’s ` toString() method. Then, Java invokes john's toString() method to convert john to a String. Now, given that albert is john's friend, albert's toString() method is called again from within john's toString()` method and the cycles starts all over again. This is a recursive call and will theoretically run forever as shown in the following image.

The above recursive call will keep going until we run out of memory and a StackOverflowError is thrown and the program crash.

albert->toString()->john->toString()->albert->toString()->john->toString()->...until we consume all memory.

The above program will fail with an StackOverflowError.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.lang.StringUTF16.checkIndex(StringUTF16.java:1587)

at java.base/java.lang.StringUTF16.charAt(StringUTF16.java:1384)

at java.base/java.lang.StringUTF16$CharsSpliterator.tryAdvance(StringUTF16.java:1194)

at java.base/java.util.stream.IntPipeline.forEachWithCancel(IntPipeline.java:163)

at java.base/java.util.stream.AbstractPipeline.copyIntoWithCancel(AbstractPipeline.java:502)

at java.base/java.util.stream.AbstractPipeline.copyInto(AbstractPipeline.java:488)

at java.base/java.util.stream.AbstractPipeline.wrapAndCopyInto(AbstractPipeline.java:474)

at java.base/java.util.stream.FindOps$FindOp.evaluateSequential(FindOps.java:150)

at java.base/java.util.stream.AbstractPipeline.evaluate(AbstractPipeline.java:234)

at java.base/java.util.stream.IntPipeline.findFirst(IntPipeline.java:528)

at java.base/java.text.DecimalFormatSymbols.findNonFormatChar(DecimalFormatSymbols.java:778)

at java.base/java.text.DecimalFormatSymbols.initialize(DecimalFormatSymbols.java:758)

at java.base/java.text.DecimalFormatSymbols.<init>(DecimalFormatSymbols.java:115)

at java.base/sun.util.locale.provider.DecimalFormatSymbolsProviderImpl.getInstance(DecimalFormatSymbolsProviderImpl.java:85)

at java.base/java.text.DecimalFormatSymbols.getInstance(DecimalFormatSymbols.java:182)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.getZero(Formatter.java:2437)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.<init>(Formatter.java:1956)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.<init>(Formatter.java:1978)

at java.base/java.lang.String.format(String.java:3302)

at demo.Person.toString(Person.java:29)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.printString(Formatter.java:3031)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.print(Formatter.java:2908)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2673)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2609)

at java.base/java.lang.String.format(String.java:3302)

at demo.Person.toString(Person.java:29)

...

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.printString(Formatter.java:3031)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.print(Formatter.java:2908)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2673)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2609)

at java.base/java.lang.String.format(String.java:3302)

at demo.Person.toString(Person.java:29)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.printString(Formatter.java:3031)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.print(Formatter.java:2908)

Following is a better example that avoids recursive toString() method.

package demo;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

private Person friend;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

public void setFriend( final Person friend ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() {

final String friendToString =

friend == null ? "no friend"

: String.format( "{name=%s, surname=%s}", friend.name, friend.surname );

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, surname=%s, friend=%s}", name, surname, friendToString );

}

}

Running the previous example will not print.

Person{name=Albert, surname=Attard, friend={name=John, surname=Ferry}}

The equals() and hashCode() methods

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person a = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person b = new Person( "Aden" );

final boolean areEquals = a.equals( b );

System.out.printf( "Are these objects equal? %s%n", areEquals );

}

}

We have two instances which have the same content, a person with the same name. What will the equals() method return?

Are these objects equal? false

Despite having the same name ("Aden") and surname (null), the equals() as defined by the Object class will only check whether the variables are pointing to the same instance in the Java heap.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person a = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person b = a;

final boolean areEquals = a.equals( b );

System.out.printf( "Are these objects equal? %s%n", areEquals );

}

}

In the above example, both variables a and b point to the same object in the Java heap. The above will print true.

Are these objects equal? true

Overriding the equals() method can help us solve this problem.

package demo;

import java.util.Objects;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.isNullOrEmpty;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public boolean equals( final Object object ) {

if ( this == object ) {

return true;

}

if ( !( object instanceof Person ) ) {

return false;

}

final Person that = (Person) object;

return Objects.equals( name, that.name ) &&

Objects.equals( surname, that.surname );

}

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

In the above example we made use of the Objects’ utilities equals() method. This method is not to be mistaken with the normal equals() method. The utilities equals() method is very useful when comparing two instance variables and is a shorthand for the following.

public static boolean equals(Object a, Object b) {

return (a == b) || (a != null && a.equals(b));

}

If we rerun the same program we had before, we will get the expected output, as our equals() method is now used.

Are these objects equal? true

The equals() method is used a lot by the Java API in conjunction with the hashCode() method. The relation between these two methods is so strong that the Effective Java book has an item about this, Item 11: Always override hashCode when you override equals.

Failing to override the hashCode() will make our class incompatible with some Java API. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.HashSet;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Set;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

/* Two persons that will be added to the collections */

final Person a = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person b = new Person( "Jade" );

/* Create two collections, list and set and put two persons in each */

final List<Person> list = List.of( a, b );

final Set<Person> set = new HashSet<>( List.of( a, b ) );

System.out.println( "-- Collections ------------" );

System.out.printf( "List: %s%n", list );

System.out.printf( "Set: %s%n", set );

/* Use different objects to search so that we do not rely on the object's identity */

final Person m = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person n = new Person( "Peter" );

/* Search the list */

System.out.println( "-- Search the list --------" );

System.out.printf( "List contains %s? %s%n", m, list.contains( m ) );

System.out.printf( "List contains %s? %s%n", n, list.contains( n ) );

/* Search the set */

System.out.println( "-- Search the set ---------" );

System.out.printf( "Set contains %s? %s%n", m, set.contains( m ) );

System.out.printf( "Set contains %s? %s%n", n, set.contains( n ) );

}

}

The above example creates two collections, a List and a HashSet to highlight a problem. Collections are covered in depth at a later stage. Running the above may (read more here if you cannot wait to understand why ‘may’ is in bold) produce the following output.

-- Collections ------------

List: [Aden, Jade]

Set: [Aden, Jade]

-- Search the list --------

List contains Aden? true

List contains Peter? false

-- Search the set ---------

Set contains Aden? false

Set contains Peter? false

List was able to find the person with name Aden, the HashSet was not.-- Search the set ---------

Set contains Aden? false

Set contains Peter? false

Hash-based classes, such as the HashSet class or the HashMap class, rely on the hashCode() together with the equals() method to function properly. The current implementation of the Person class may work or may not work, depends on how lucky we get with the value returned by the Object’s version of the hashCode() method.

Following is a better version of the Person class.

package demo;

import java.util.Objects;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.isNullOrEmpty;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public boolean equals( final Object object ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash( name, surname );

}

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

Note that both the overridden methods equals() and hashCode() made use of the Objects.equals() and Objects.hash() methods.

The equals() and hashCode() methods are very important methods as these are extensively used by other classes. Effective Java talks in detail about this in Item 10: Obey the general contract when overriding equals. Following are some important rules related to the equals() method.

Reflexive: An object is always equal to itself.

a.equals(a)always returntrue.Symmetry: If an object,

a, is equal to another object,b, then the second objectbmust also be equal to the first objecta.When Returns Then Must a.equals(b)trueb.equals(a)truea.equals(b)falseb.equals(a)falseTransitive: If an object,

a, is equal to another object,b, and the second objectbis equals to yet another object,c, then the first objectamust also be equal to the third objectc.When Returns And Returns Then Must a.equals(b)trueb.equals(c)truea.equals(c)truea.equals(b)trueb.equals(c)falsea.equals(c)falsea.equals(b)falseb.equals(c)truea.equals(c)falseConsistent: If two objects are equal at one point in time, and nothing has changed in the meantime, these objects should remain equal.

As mentioned in Effective Java, the

URLclass “relies on comparison of the IP addresses of the hosts associated with the URLs. Translating a host name to an IP address can require network access, and it isn’t guaranteed to yield the same results over time. This can cause the URL equals method to violate the equals contract and has caused problems in practice. The behavior of URL’s equals method was a big mistake and should not be emulated. Unfortunately, it cannot be changed due to compatibility requirements. To avoid this sort of problem, equals methods should perform only deterministic computations on memory-resident objects.“

(reference)No external influence: An object should not rely on external factors to determine whether two objects are equal or not, for the reasons described above.

No object is equal to

null: An objectais never equal tonull.

a.equals(null)always returnfalse.

The above rules do not mention the relation between the outcome of the equals() method and the outcome of the hashCode() method. Following is a set of rules that govern this relation.

Consistent: The hash code value of an object should remain the same throughout the execution of the program, as long as the object does not change.

The hash code value of an object can change between different executions of the program.

If equal, same hash code: If two objects,

aandb, are equal, then these two objects must have the same hash code value.When Returns Then Must a.equals(b)truea.hashCode() == b.hashCode()trueIf same hash code, not necessarily equal. Hash code does not replace equality as two objects may have the same hash code and not be equal.

When Returns Then May be a.hashCode() == b.hashCode()truea.equals(b)truea.hashCode() == b.hashCode()truea.equals(b)falseNote that if two objects have a different hash code value, then these objects must not be equal.

When Returns Then Must a.hashCode() == b.hashCode()falsea.equals(b)false

Be careful with recursive equals() (and hashCode()) calls

This is very similar to Be careful with recursive toString() calls section.

Consider the following example.

StackOverflowError!! package demo;

import java.util.Objects;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

private Person friend;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

public void setFriend( final Person friend ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public boolean equals( final Object object ) {

if ( this == object ) {

return true;

}

if ( !( object instanceof Person ) ) {

return false;

}

final Person that = (Person) object;

return Objects.equals( name, that.name ) &&

Objects.equals( surname, that.surname ) &&

/* ⚠️ There is a cyclic dependency which may cause a StackOverflowError!! s*/

Objects.equals( friend, that.friend );

}

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash( name, surname, friend );

}

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

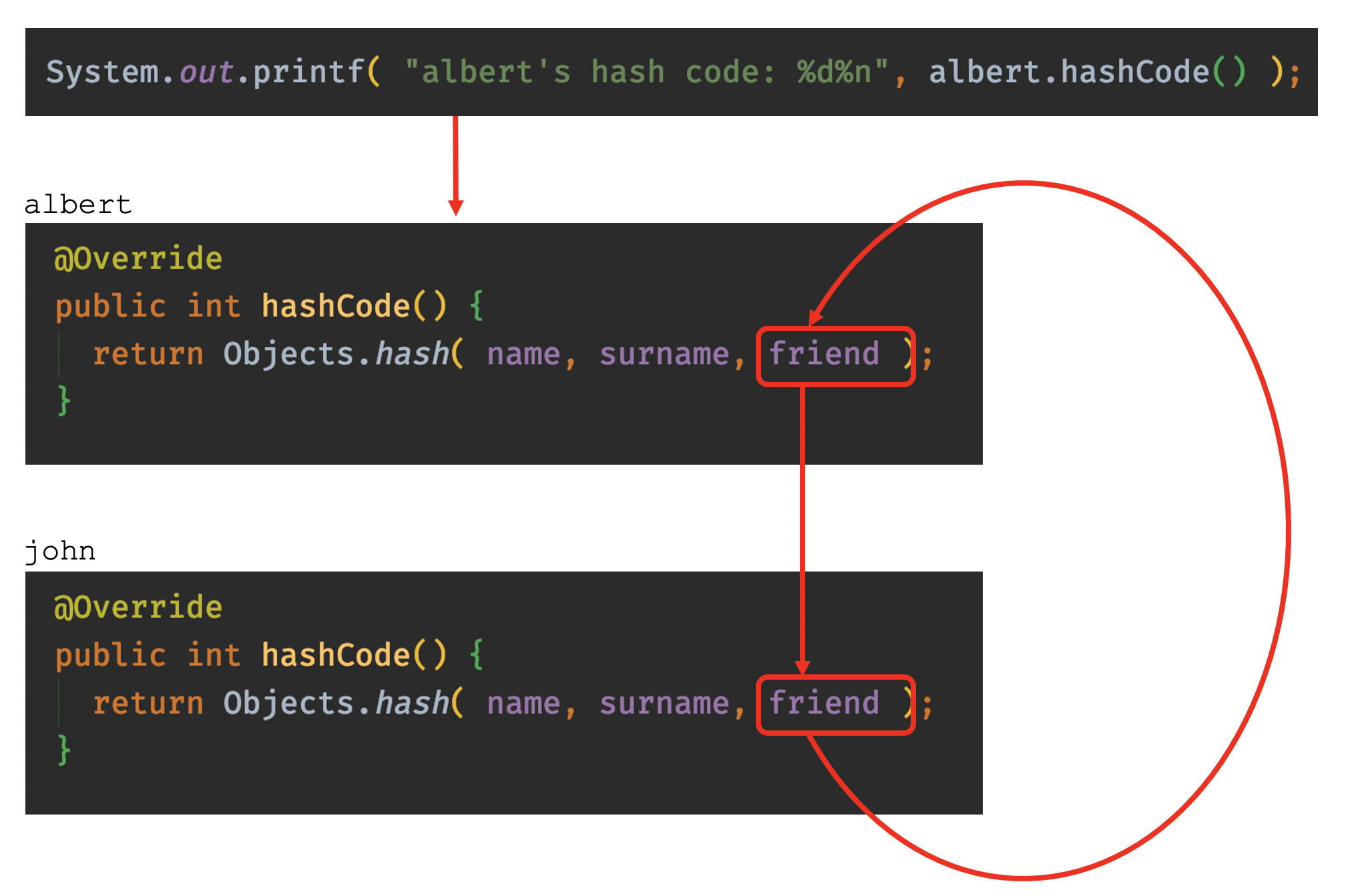

Invoking the hashCode() function will cause a recursive chain that will only stop by the program crashing with a StackOverflowError.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person albert = new Person( "Albert", "Attard" );

final Person john = new Person( "John", "Ferry" );

/* Albert and John are friends */

albert.setFriend( john );

john.setFriend( albert );

System.out.printf( "albert's hash code: %d%n", albert.hashCode() );

}

}

The following image shows how this deadly friendship cases an infinite recursive call.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.util.Arrays.hashCode(Arrays.java:4498)

at java.base/java.util.Objects.hash(Objects.java:147)

at demo.Person.hashCode(Person.java:48)

at java.base/java.util.Arrays.hashCode(Arrays.java:4498)

at java.base/java.util.Objects.hash(Objects.java:147)

..

at demo.Person.hashCode(Person.java:48)

at java.base/java.util.Arrays.hashCode(Arrays.java:4498)

Same applies to the equals() method. The example that triggers this problem is a bit more elaborate as we need to create a matching pair of objects which will cause the equals() to enter into a deadly recursive dance.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person albert = new Person( "Albert", "Attard" );

final Person john = new Person( "John", "Ferry" );

/* Albert and John are friends */

albert.setFriend( john );

john.setFriend( albert );

/* Another version of Albert and John */

final Person anotherAlbert = new Person( "Albert", "Attard" );

final Person anotherJohn = new Person( "John", "Ferry" );

anotherAlbert.setFriend( anotherJohn );

anotherJohn.setFriend( anotherAlbert );

System.out.printf( "Are equal? %s%n", albert.equals( anotherAlbert ) );

}

}

As expected, the equals() methods will enter a recursive call that will only end by the program crashing with a StackOverflowError.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BmpCharPredicate.lambda$union$2(Pattern.java:5646)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BmpCharPredicate.lambda$union$2(Pattern.java:5646)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BmpCharProperty.match(Pattern.java:3973)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$GroupHead.match(Pattern.java:4809)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Branch.match(Pattern.java:4752)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Branch.match(Pattern.java:4752)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Branch.match(Pattern.java:4752)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BranchConn.match(Pattern.java:4718)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$GroupTail.match(Pattern.java:4840)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BmpCharPropertyGreedy.match(Pattern.java:4349)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$GroupHead.match(Pattern.java:4809)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Branch.match(Pattern.java:4754)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Branch.match(Pattern.java:4752)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$BmpCharProperty.match(Pattern.java:3974)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Pattern$Start.match(Pattern.java:3627)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Matcher.search(Matcher.java:1729)

at java.base/java.util.regex.Matcher.find(Matcher.java:773)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.parse(Formatter.java:2702)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2655)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2609)

at java.base/java.lang.String.format(String.java:3302)

at demo.Person.toString(Person.java:55)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.printString(Formatter.java:3031)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter$FormatSpecifier.print(Formatter.java:2908)

at java.base/java.util.Formatter.format(Formatter.java:2673)

at java.base/java.io.PrintStream.format(PrintStream.java:1209)

at java.base/java.io.PrintStream.printf(PrintStream.java:1105)

at demo.Person.equals(Person.java:31)

at java.base/java.util.Objects.equals(Objects.java:78)

...

at java.base/java.util.Objects.equals(Objects.java:78)

at demo.Person.equals(Person.java:43)

at java.base/java.util.Objects.equals(Objects.java:78)

at demo.Person.equals(Person.java:43)

How can we avoid this problem?

There are several approaches to address this problem.

Do not have the

friendproperty (or any other property that leads to recursive calls) as part of the equality/hash computationpackage demo; import java.util.Objects; public class Person { private final String name; private final String surname; private Person friend; public Person() { /* ... */ } public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ } public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ } public void setFriend( final Person friend ) { /* ... */ } @Override public boolean equals( final Object object ) { if ( this == object ) { return true; } if ( !( object instanceof Person ) ) { return false; } final Person that = (Person) object; return Objects.equals( name, that.name ) && Objects.equals( surname, that.surname ); } @Override public int hashCode() { return Objects.hash( name, surname ); } @Override public String toString() { /* ... */ } }Refactor the classes such that it avoids recursive calls

Create a class that represents friendship.

package demo; import java.util.Objects; public class Friendship { private final Person a; private final Person b; public Friends( final Person a, final Person b ) { this.a = a; this.b = b; } @Override public boolean equals( final Object object ) { if ( this == object ) { return true; } if ( !( object instanceof Friends ) ) { return false; } final Friends that = (Friends) object; return Objects.equals( a, that.a ) && Objects.equals( b, that.b ); } @Override public int hashCode() { return Objects.hash( a, b ); } @Override public String toString() { return String.format( "Friendship{a=%s, b=%s}", a, b ); } }Remove the

friendproperty from thePersonclass.package demo; import java.util.Objects; public class Person { private final String name; private final String surname; public Person() { /* ... */ } public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ } public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ } @Override public boolean equals( final Object object ) { if ( this == object ) { return true; } if ( !( object instanceof Person ) ) { return false; } final Person that = (Person) object; return Objects.equals( name, that.name ) && Objects.equals( surname, that.surname ); } @Override public int hashCode() { return Objects.hash( name, surname ); } @Override public String toString() { return String.format( "Person{name=%s, surname=%s}", name, surname ); } }

There may be other valid approaches that avoid recursive calls.

The getClass() method

An object is an instance of a class. Thus, all objects have a class and this can be retrieved using the getClass() method. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.awt.Point;

import java.util.Random;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Object a = new Point( 1, 2 );

final Object b = new Random();

printType( a );

printType( b );

}

private static void printType( final Object object ) {

System.out.printf( "The object is of type %s%n", object.getClass() );

}

}

The above will print

The object is of type class java.awt.Point

The object is of type class java.util.Random

The class, of any object, can be also obtained from the actual class name (or primitive type) using the class literal (as defined by JLS-15.8.2). For example, we can obtain the class of the Point class using the class literal Point.class. The class itself is represented as a Java object in Java.

package demo;

import java.awt.Point;

import java.util.Random;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Object a = new Point( 1, 2 );

final Object b = new Random();

isOfPointType( a );

isOfPointType( b );

}

private static void isOfPointType( final Object object ) {

final boolean isSameClass = Point.class == object.getClass();

System.out.printf( "Is the object (%s) of type Point? %s%n", object.getClass(), isSameClass );

}

}

The above will print

Is the object (class java.awt.Point) of type Point? true

Is the object (class java.util.Random) of type Point? false

The getClass(), class and the equals() method

The getClass() method is sometimes used in the equals() method in (false) hope to make the comparison more efficient.

package demo;

import java.util.Objects;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final String surname;

public Person() { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name ) { /* ... */ }

public Person( final String name, final String surname ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public boolean equals( final Object object ) {

if ( this == object ) {

return true;

}

// if ( !( object instanceof Person ) ) {

if ( object == null || object.getClass() != getClass() ) {

return false;

}

final Person that = (Person) object;

return Objects.equals( name, that.name ) &&

Objects.equals( surname, that.surname );

}

@Override

public int hashCode() { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

equals() method is slightly different from the previous version. Instead of using the instanceof operator we are comparing the classes. The above works exactly like the one before, when we used the instanceof. Now, consider the following code fragment. if ( object == null || object.getClass() != Person.class ) {

The above is not equivalent to the one saw before and will produce unexpected results when we extend the Person class.

package demo;

public class VeryImportantPerson extends Person {

public VeryImportantPerson( final String name, final String surname ) {

super( name, surname );

}

}

Consider the following three objects.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final VeryImportantPerson a = new VeryImportantPerson( "Aden", "Attard" );

final VeryImportantPerson b = new VeryImportantPerson( "Aden", "Attard" );

final Person c = new Person( "Aden", "Attard" );

System.out.printf( "Are these equal? %s%n", a.equals( b ) );

System.out.printf( "Are these equal? %s%n", a.equals( c ) );

}

}

All three instances have the same name and surname, yet the wrong pair evaluates to true as shown next.

Are these equal? false

Are these equal? true

This example also breaks the equals() contract as the above is not reflective. This is a typical example of premature optimisation is the root of evil.

The wait(), notify() and notifyAll() methods

Java supported multithreading since its early days (more than 25 years ago). When working with threads, we may need to wait for something to happen before continuing. Say we have a doctor’s appointment. We go to the clinic, register at the desk and then wait for our name to be called. This can be achieved using any of the wait() methods.

The following example simulates a patient visiting the doctor and waiting for their name to be called. The following example make use of multithreading.

package demo;

import java.time.LocalTime;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person patient = new Person( "Aden" );

waitInLobby( patient );

letSomeTimePass();

callNext( patient );

}

private static void waitInLobby( final Person patient ) {

final Thread t = new Thread( () -> {

synchronized ( patient ) {

try {

display( "Waiting in the lobby for my name to be called" );

patient.wait();

display( "My name was called!!" );

} catch ( InterruptedException e ) { }

}

}, "waiting in lobby" );

t.start();

}

private static void letSomeTimePass() {

try {

display("letting some time pass…");

Thread.sleep( 500 );

} catch ( InterruptedException e ) { }

}

private static void callNext( final Person patient ) {

synchronized ( patient ) {

displayf( "%s, the doctor is ready to see you", patient );

patient.notifyAll();

}

}

private static void displayf( final String pattern, final Object... parameters ) {

display( String.format( pattern, parameters ) );

}

private static void display( final String message ) {

System.out.printf( "%s [%s] %s%n", LocalTime.now(), Thread.currentThread().getName(), message );

}

}

Break down of the above example.

The

main()method is fairly straight forward. An object of typePersonis created and passed to thewaitInLobby()method. TheletSomeTimePass()method is called next followed by thecallNext()method.public static void main( final String[] args ) { final Person patient = new Person( "Aden" ); waitInLobby( patient ); letSomeTimePass(); callNext( patient ); }The

waitInLobby()method is harder to understand.private static void waitInLobby( final Person patient ) { final Thread t = new Thread( () -> { synchronized ( patient ) { try { display( "Waiting in the lobby to be called" ); patient.wait(); display( "My name was called!!" ); } catch ( InterruptedException e ) { } } }, "waiting in lobby" ); t.start(); }The method starts by creating a thread,

t, which will be used to wait. A new thread is required as when thewait()method is invoked, the thread from which the method is called, is paused until thenotify()ornotifyAll()methods are called on the same object. If we invoke thewait()on the main thread, our program may hang forever.The

wait()method need to be invoked within asynchronizedblock. Each object (not primitives) in Java has an intrinsic lock, that can be used to control the access to this object by other threads. If an object needs to be modified by multiple threads, thesynchronizedblock can be used so that the threads do not step on each other and put the object in an inconsistent state.The

wait()method will pause the current thread indefinitely. The overloaded versions of this method provide a timeout to prevent threads from hanging there forever.Like most of the concurrent operations, the

wait()method may throw anInterruptedExceptionif it is interrupted while waiting which need to be caught. Using thewait()method outside asynchronizedblock will throw anIllegalMonitorStateException.The

letSomeTimePass()pauses the current thread for 500 milliseconds.private static void letSomeTimePass() { try { display("letting some time pass…"); Thread.sleep( 500 ); } catch ( InterruptedException e ) { } }Similar to the

wait()method, the thread which is sleeping may be interrupted, in which case anInterruptedExceptionis thrown.The

callNext()method obtains the lock on the person using thesynchronizedblock and then invoked thenotifyAll()method.private static void callNext( final Person patient ) { synchronized ( patient ) { displayf( "%s, the doctor is ready to see you", patient ); a.notifyAll(); } }The

notifyAll()method notifies all threads that the object (the object to which variablepatientpoints to) is ready to wake up and resume operation. This will cause thewait()method to stop waiting and unblocks the other thread (created in thewaitInLobby()method). Thenotify()method behaves similarly to thenotifyAll()with the difference that only one thread is notified and not all threads. If the notified thread is not the right thread (not the thread that was blocked waiting), then the notification is lost, and the blocked thread will hang waiting forever. It is always recommended to use thenotifyAll()method instead of thenotify()method.

The example prints the following.

12:34:56.000022 [waiting in lobby] Waiting in the lobby for my name to be called

12:34:56.000000 [main] letting some time pass…

12:34:56.482630 [main] Aden, the doctor is ready to see you

12:34:56.483048 [waiting in lobby] My name was called!!

A small observation regarding the messages order. Note that the second message happened before the first message by some nano seconds, yet it appears after the first message. Note that the text within the square brackets, waiting in lobby and main, represents the thread’s name from where the message is printed. The example made use of two threads, the main thread and a second thread, named waiting in lobby.

The approach to multithreading in Java has been revised and a new concurrency API was added to the language. The new concurrency API provider better concurrency primitives and is always recommended over intrinsic locking, shown above.