Inheritance

Table of contents

- Inheritance

- Extending the

Boxfunctionality (creating and evolving theLightBoxclass step by step) - Can we add items to a box if the box is not open?

- Can we design our classes to automatically prevents the object from going into invalid state (finite state machine)?

- Create the

HeavyBox(complete example) - How can a subclass invoke a method in the parent class (the

superkeyword)? - Can we prevent a class from being extended (the

finalkeyword)? - Are constructors inherited?

- How do

privateconstructor effect inheritance? - Can a subclass invoke the constructor of a superclass (the

super())? - Can a constructor in a parent class call a method in a subclass?

- What happens when not all ‘children’ are ‘parents’?

- Is inheritance evil and should be considered as an anti-pattern?

Inheritance

There are two types of boxes. The light boxes, which are boxes that can contain only one item. The heavy boxes can contain more than one item. Both boxes can be open or closed and change their label using the methods created before.

Extending the Box functionality (creating and evolving the LightBox class step by step)

Create the

LightBoxpackage demo; public class LightBox { }Like a box, the light box can be opened and closed and has a label too. The light box has all features the box has and can be seen as an extended version of the box. Note that a light box can only contain one item. A light box is empty if it has no item, otherwise non-empty. We should not be able to add an item to a non-empty box.

We have several options here. We can either replicate all properties and methods to the new class, or inherit all of it from the

Boxclass. Both options are shown next.Replicate

package demo; import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkArgument; import static com.google.common.base.Strings.nullToEmpty; public class LightBox { private BoxForm form; private String label = "No Label"; public Box() { /* ... */ } public Box( final BoxForm form ) { /* ... */ } public void open() { /* ... */ } public void close() { /* ... */ } public boolean isOpen() { /* ... */ } public String getLabel() { /* ... */ } public void changeLabelTo( final String label ) { /* ... */ } private static boolean isValidLabel( final String label ) { /* ... */ } @Override public String toString() { /* ... */ } public enum BoxForm { /* ... */ } }Inherit

package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { }

Given that the light box is a specific type of box, it is safe to inherit from box.

The

LightBoxclass inherits from (orextends) theBoxclass. TheBoxclass is referred to as the super class while theLightBoxclass is known as the child class (or the subclass).package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { final LightBox a = new LightBox(); final Box b = new LightBox(); a.open(); b.close(); System.out.printf( "Box a: %s%n", a ); System.out.printf( "Box b: %s%n", b ); } }All methods and state available to a

Boxobject is also available to aLightBoxobject.Box a: an open box Box b: a closed boxNote that all light boxes are boxes, and this is quite an important statement when dealing with inheritance.

Note that the opposite does not hold. In other words, NOT all boxes are light boxes. Fruit is a good analogy to this. All apples are fruit but not all fruit is apples. Shapes are another good example. All circles are shape, but not all shapes are circle.

The following will not compile.

final LightBox a = new Box();Add the

isEmpty()methodWe can only place an item in a light box if this is empty. Adding this functionality before the ability to add an item to the box seems more natural since that the latter relies on the box being empty.

package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; public class LightBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); assertTrue( box.isEmpty() ); } }Add the missing method (without any special logic) just to make the program compile.

package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { public boolean isEmpty() { return true; } }Run the tests. All tests should pass.

Add the ability to add an item’s id (of type

long) to theLightBox.The light box should not be empty (the

isEmpty()method should returnfalse) once an item is placed in the box.Create the test

package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; public class LightBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" ) public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); box.putItem( 1 ); assertFalse( box.isEmpty() ); } }Add the missing method (without any special logic) just to make the program compile.

package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { public boolean isEmpty() { /* ... */ } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { } }Run the tests. The second test will fail as expected.

$ ./gradlew test ... LightBoxTest > should not be empty when an item is placed in the box FAILED org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError at LightBoxTest.java:23 ...Add state to the

LightBoxclass.Like many things in programming, we can take different approaches.

Using enums (preferred approach)

package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { private Space space = Space.AVAILABLE; public boolean isEmpty() { return space == Space.AVAILABLE; } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { space = Space.FULL; } private enum Space { AVAILABLE, FULL } }Using

boolean(a very common approach)package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { private boolean empty = true; public boolean isEmpty() { return empty; } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { empty = false; } }

What happens to the

itemIdvalue passed to theputItem()method? We are not storing this value anywhere just yet as we don’t have a test that retrieves theitemId. Always do the bare minimum just to get the test working!!Sometimes a property is used for various purposes. Instead of creating a new property, (

spaceorempty, depending with approach you took), we could use theitemIdproperty, as shown in the following example.⚠️ NOT RECOMMENDED!!

package demo; public class LightBox extends Box { public static final long EMPTY = -1L; private long itemId = EMPTY; public boolean isEmpty() { return itemId == EMPTY; } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { this.itemId = itemId; } }The property

itemIdis used for two purposes and that’s discouraged. If negative IDs become valid, for any reason, this logic becomes invalid.A light box can only contain one item and an

IllegalStateExceptionshould be thrown if an item is added to a non-empty box.package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertThrows; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; public class LightBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" ) public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenNotEmpty() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); box.putItem( 1 ); assertThrows( IllegalStateException.class, () -> box.putItem( 1 ) ); } }The test should fail.

$ ./gradlew test ... LightBoxTest > should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box FAILED org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError at LightBoxTest.java:32 ...Fix failing tests

package demo; import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState; public class LightBox extends Box { private Space space = Space.AVAILABLE; public boolean isEmpty() { /* ... */ } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { checkState( isEmpty() ); space = Space.FULL; } private enum Space { /* ... */ } }Note that we are now using the

checkState()method instead of thecheckArguments()method as we need to fail with anIllegalStateExceptionwhen the light box already contains an item.Tests should pass now.

Can we add items to a box if the box is not open?

No, our program should throw an IllegalStateException if the putItem() method is called on a LightBox instance that is not open. We can only add an item to the box when the box is open.

Start by adding a test

package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertThrows; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assumptions.assumeFalse; public class LightBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" ) public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenNotEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should throw an IllegalStateException when trying to adding an item to a non-open box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenClosed() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); assumeFalse( box.isOpen() ); assertThrows( IllegalStateException.class, () -> box.putItem( 1 ) ); } }Note that the above test, makes use of the

assumeFalse()method instead of theassertFalse()method as this is a precondition and not the actual test. In this case, we are assuming that the box is closed by default.The above test will fail.

Check whether the box is open before adding an item to it.

package demo; import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState; public class LightBox extends Box { private Space space = Space.AVAILABLE; public boolean isEmpty() { /* ... */ } public void putItem( final long itemId ) { checkState( isOpen() ); checkState( isEmpty() ); space = Space.FULL; } private enum Space { /* ... */ } }Alternatively we can have both check in one statement

checkState( isOpen() && isEmpty() );Run the tests

$ ./gradlew test > Task :test FAILED BoxTest > should be open after the open method is called PASSED BoxTest > should not be open after the close method is called PASSED LightBoxTest > should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed PASSED LightBoxTest > should throw an IllegalStateException when trying to adding an item to a non-open box PASSED LightBoxTest > should not be empty after an item is placed in the box FAILED java.lang.IllegalStateException at LightBoxTest.java:23 LightBoxTest > should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box FAILED java.lang.IllegalStateException at LightBoxTest.java:31 6 tests completed, 2 failed ...To our surprise, we broke more tests than we fixed. Some of the previous tests were adding items to a closed box.

When you encounter such a case, do not rush and change the tests. Instead, make sure that the changes that will be made to the tests will not break any of the existing functionality. Always discuss such changes with the rest of the team.

We know that we should not be able to add items to a closed box, in which case we can update the previous tests to have the box in the proper state.

package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertThrows; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assumptions.assumeFalse; public class LightBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { /* ... */ } @Test @DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" ) public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); box.open(); box.putItem( 1 ); assertFalse( box.isEmpty() ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenNotEmpty() { final LightBox box = new LightBox(); box.open(); box.putItem( 1 ); assertThrows( IllegalStateException.class, () -> box.putItem( 1 ) ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should throw an IllegalStateException when trying to adding an item to a non-open box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenClosed() { /* ... */ } }

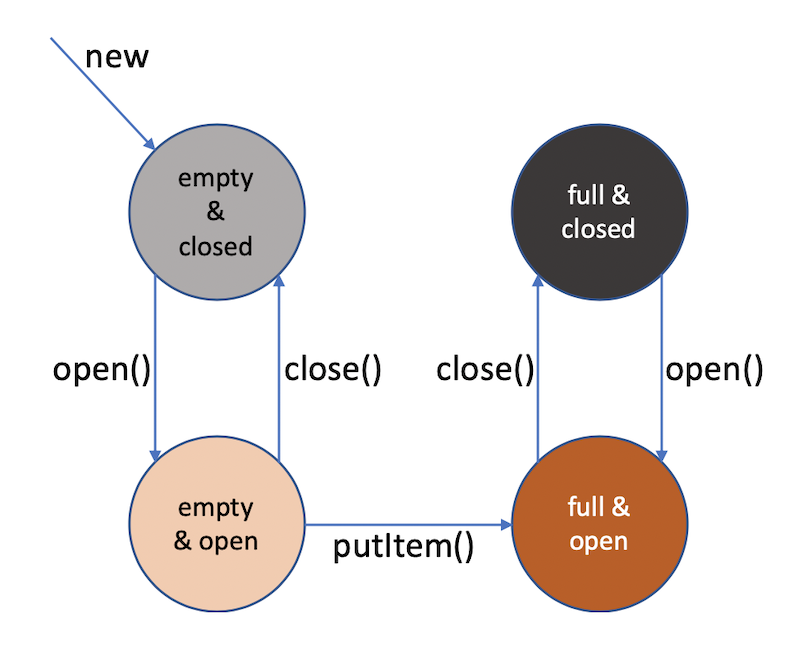

Can we design our classes to automatically prevents the object from going into invalid state (finite state machine)?

Yes. We can design our classes such that our objects can never be in an invalid state. This approach moves towards functional programming. Our light box can be in either open/close and empty/full state.

| # | Open/Closed | Empty/Full |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | OPEN | EMPTY |

| 2 | OPEN | FULL |

| 3 | CLOSED | FULL |

| 4 | CLOSED | EMPTY |

This is captured by the following State-Transition Diagrams.

Consider the following (more complicated) version of the LightBox class.

package demo;

import java.util.Optional;

public class LightBox {

private Optional<Long> itemId = Optional.empty();

public static CloseEmpty newBox() {

return new LightBox().closeEmpty;

}

public class CloseEmpty {

public OpenEmpty open() {

return openEmpty;

}

}

public class OpenEmpty {

public CloseEmpty close() {

return closeEmpty;

}

public OpenFull putItem( final long itemId ) {

LightBox.this.itemId = Optional.of( itemId );

return openFull;

}

}

public class CloseFull {

public OpenFull open() {

return openFull;

}

}

public class OpenFull {

public CloseFull close() {

return closeFull;

}

}

private final CloseEmpty closeEmpty = new CloseEmpty();

private final OpenEmpty openEmpty = new OpenEmpty();

private final CloseFull closeFull = new CloseFull();

private final OpenFull openFull = new OpenFull();

private LightBox() {

}

}

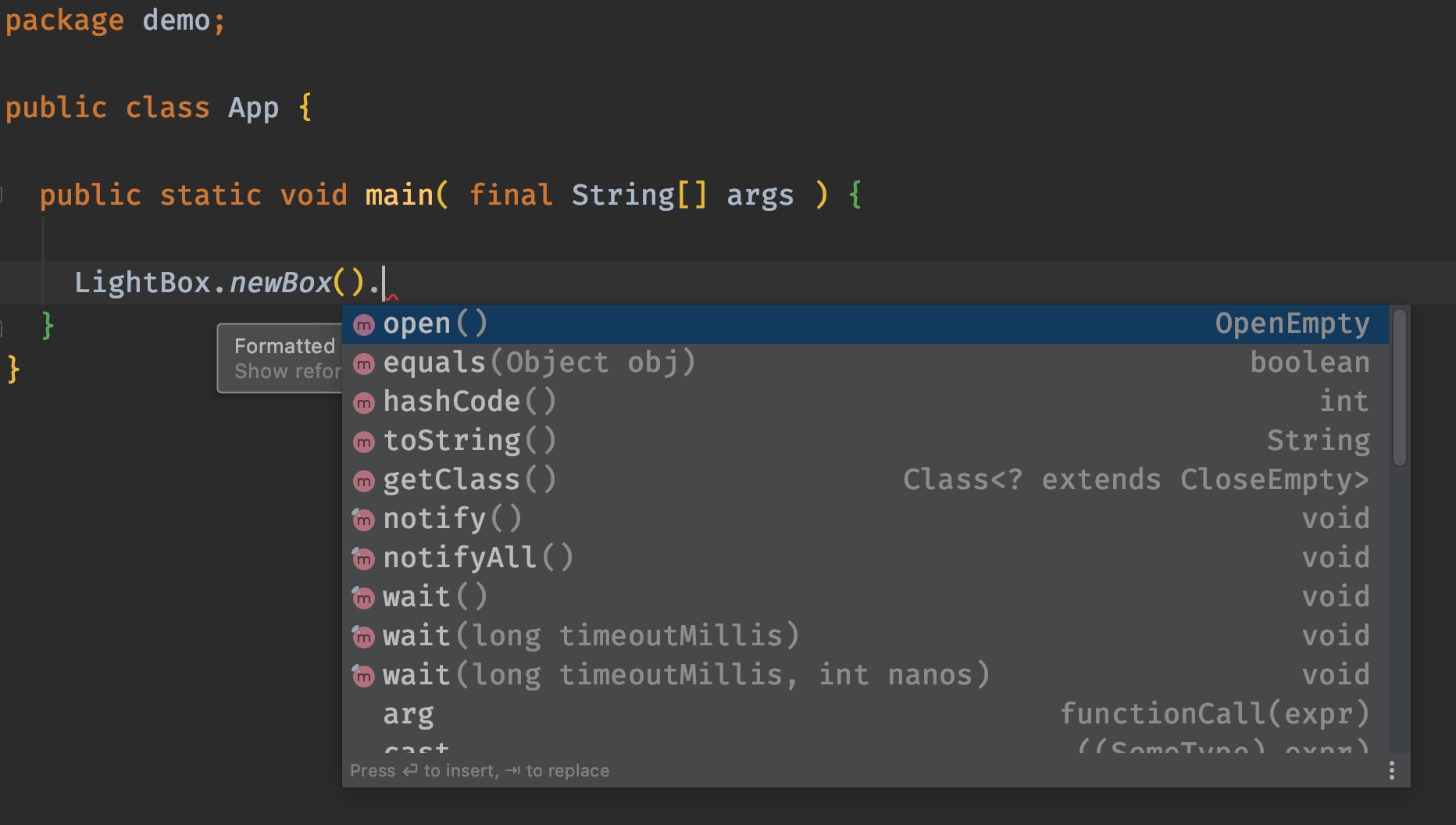

This is quite complex, so let’s break it into smaller parts.

Force the box to start in a close/empty state.

We can use static factory methods to create an instance of box and then return in the box in the desired state.

public static CloseEmpty newBox() { return new LightBox().closeEmpty; }Note that the constructor is

privateso that the class is only created using the static factory methods.private LightBox() { }Each state is captured by an inner class, which only exposes the methods that are relevant to the current state.

An empty/closed box can only be opened.

public class CloseEmpty extends LightBox { public OpenEmpty open() { return openEmpty; } }An empty/open box can be closed or an item be added to it.

public class OpenEmpty extends LightBox { public CloseEmpty close() { return closeEmpty; } public OpenFull putItem( final long itemId ) { return openFull; } }The inner classes can access the properties of the class. Note that each method within the inner classes is returning a property defined within the outer class.

Following is an example of how this can be used.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final LightBox.CloseFull a = LightBox.newBox()

.open()

.putItem( 1L )

.close();

}

}

While this look very promising, it is quite hard program in this fashion and not quite common in Java. The above example has a flaw as we can save the state and invoked one of the methods that belong to that state more than once. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final LightBox.EmptyOpen emptyOpen = LightBox.newBox().open();

emptyOpen.putItem( 1L );

emptyOpen.putItem( 2L );

}

}

The above code compiles and works, and the second item will replace the first item. That’s not the expected behaviour. The light box’s current state needs to be captured and checked before executing any action. Consider the following finite state machine.

package demo.complete;

import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState;

public class FiniteStateMachine {

private State activeState;

public FiniteStateMachine( final State initialState ) {

this.activeState = initialState;

}

public <T extends State> T changeState( State current, T next, Runnable block ) {

checkState( current == activeState );

block.run();

activeState = next;

return next;

}

public <T extends State> T changeState( State current, T next ) {

return changeState( current, next, BLANK );

}

private static final Runnable BLANK = () -> { };

public interface State { }

}

This is a generic state machine that first checks whether the action being executed belongs to the current state or not. Using our previous example, once the item is added (through the putItem() method), the light box should now be in the full/open state. Therefore, we should not be able to invoke the putItem() method for the second time.

We can refactor the LightBox class and use the finite state machine created before.

package demo;

import demo.complete.FiniteStateMachine;

import java.util.Optional;

public class LightBox {

private Optional<Long> itemId = Optional.empty();

public static EmptyClosed newBox() { /* ... */ }

public class EmptyClosed implements FiniteStateMachine.State {

public EmptyOpen open() {

return stateMachine.changeState( this, emptyOpen );

}

}

public class EmptyOpen implements FiniteStateMachine.State {

public EmptyClosed close() {

return stateMachine.changeState( this, emptyClosed );

}

public FullOpen putItem( final long itemId ) {

return stateMachine.changeState( this, fullOpen, () -> {

LightBox.this.itemId = Optional.of( itemId );

} );

}

}

public class FullOpen implements FiniteStateMachine.State {

public FullClosed close() {

return stateMachine.changeState( this, fullClosed );

}

}

public class FullClosed implements FiniteStateMachine.State {

public FullOpen open() {

return stateMachine.changeState( this, fullOpen );

}

}

private final EmptyClosed emptyClosed = new EmptyClosed();

private final EmptyOpen emptyOpen = new EmptyOpen();

private final FullOpen fullOpen = new FullOpen();

private final FullClosed fullClosed = new FullClosed();

private final FiniteStateMachine stateMachine = new FiniteStateMachine( emptyClosed );

private LightBox() { }

}

Using the finite state machine, only the active state can invoke method. Trying to invoke a method through a non-active state will throw an IllegalStateException.

IllegalStateException!! package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final LightBox.EmptyOpen emptyOpen = LightBox.newBox().open();

emptyOpen.putItem( 1L );

emptyOpen.putItem( 2L );

}

}

Rerunning the same code will now throw an IllegalStateException.

As mentioned before, while the final state machine provides some advantages, it adds a level of complexity.

Create the HeavyBox (complete example)

A heavy box is a box that can take more than one item.

Tests class

package demo; import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName; import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertThrows; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue; import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assumptions.assumeFalse; public class HeavyBoxTest { @Test @DisplayName( "should be empty when creating a new heavy box and no items are placed" ) public void shouldBeEmpty() { final HeavyBox box = new HeavyBox(); assertTrue( box.isEmpty() ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" ) public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { final HeavyBox box = new HeavyBox(); box.open(); box.addItem( 1 ); assertFalse( box.isEmpty() ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should allow multiple items in the box" ) public void shouldAllowMultipleItems() { final HeavyBox box = new HeavyBox(); box.open(); box.addItem( 1 ); box.addItem( 2 ); box.addItem( 3 ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalArgumentException when adding an item that is already in the box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenItemAlreadyExists() { final HeavyBox box = new HeavyBox(); box.open(); box.addItem( 1 ); assertThrows( IllegalArgumentException.class, () -> box.addItem( 1 ) ); } @Test @DisplayName( "should throw an IllegalStateException when trying to adding an item to a non-open box" ) public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenClosed() { final HeavyBox box = new HeavyBox(); assumeFalse( box.isOpen() ); assertThrows( IllegalStateException.class, () -> box.addItem( 1 ) ); } }Heavy box class

package demo; import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkArgument; import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState; public class HeavyBox extends Box { private final List<Long> items = new ArrayList<>(); public boolean isEmpty() { return items.isEmpty(); } public void addItem( final long itemId ) { checkState( isOpen() ); checkArgument( false == items.contains( itemId ) ); items.add( itemId ); } }

How can a subclass invoke a method in the parent class (the super keyword)?

While heavy boxes may contain very long labels, light box labels cannot be longer than 32 letters long. Trying to set longer labels should throw an IllegalArgumentException. The LightBox class needs to check the label’s length before passing it to the parent class to set it.

package demo;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.DisplayName;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertFalse;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertThrows;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assmueFalse;

public class LightBoxTest {

@Test

@DisplayName( "should be empty when a new light box is created and no items are yet placed" )

public void shouldBeEmpty() { /* ... */ }

@Test

@DisplayName( "should not be empty after an item is placed in the box" )

public void shouldNotBeEmpty() { /* ... */ }

@Test

@DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalStateException when adding an item to a non-empty box" )

public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenNotEmpty() { /* ... */ }

@Test

@DisplayName( "should throw an IllegalStateException when trying to adding an item to a non-open box" )

public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenClosed() { /* ... */ }

@Test

@DisplayName( "should thrown an IllegalArgumentException when given a label longer than 32 letters" )

public void shouldThrowExceptionWhenGivenLongLabels() {

final LightBox box = new LightBox();

assertThrows( IllegalArgumentException.class, () -> box.changeLabelTo( "123456789 123456789 123456789 123" ) );

}

}

The changeLabelTo() method can be overridden and a new validation added as shown next.

package demo;

import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkArgument;

import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.nullToEmpty;

public class LightBox extends Box {

private Space space = Space.AVAILABLE;

public boolean isEmpty() { /* ... */ }

public void putItem( final long itemId ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public void changeLabelTo( final String label ) {

checkArgument( isValidLabel( label ) );

super.changeLabelTo( label );

}

private static boolean isValidLabel( final String label ) {

return nullToEmpty( label ).length() <= 32;

}

private enum Space { /* ... */ }

}

The changeLabelTo() in the LightBox cannot set the label directly as this belongs to the Box class. A child class can access its parent’s methods using the super keyword. Without the super keyword, the above method will call itself recursively until a StackOverflowException is thrown.

Should we talk about why we are not overriding isValidLabel() instead?

Can we prevent a class from being extended (the final keyword)?

Java allows a class to extend another class by default. The LightBox was able to extend the Box class without having to do anything to the Box class. This can be prevented by the final keyword, as shown next.

package demo;

import com.google.common.base.Preconditions;

import com.google.common.base.Strings;

public final class LightBox extends Box { /* ... */ }

The LightBox class cannot be extended by another class as the LightBox class is marked final. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class FeatherBox extends LightBox { /* ... */ }

The FeatherBox cannot extend LightBox as the latter is marked as final.

Are constructors inherited?

Constructors are not inherited. A subclass can invoke the parent’s constructors, but it does not inherit them.

The Box class provides two constructors, a default constructor and a constructor that takes a Box. parameter. The LightBox and the HeavyBox do not have constructors, therefore a default is added to each respectively. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import static demo.Box.BoxForm.OPEN;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Box a = new Box( OPEN );

final LightBox b = new LightBox( OPEN );

}

}

While the Box class have a constructor that accepts a boolean parameter, the LightBox class only has the given default (do nothing) constructor. A class inherits the instance methods from the parent class, and its parents, but constructors are not inherited.

How do private constructor effect inheritance?

For a class to be extended, the subclass needs to have access to at least one of the parent’s class constructors. Consider the following class.

package demo;

public class Parent {

private Parent() {

}

}

The class is not final, but still cannot be extended by another class as its sole constructor is private.

package demo;

public class Child extends Parent {

}

There are no constructors visible to class Child in the parent class Parent, therefore, the above will not compile. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class Parent {

public static class InnerChild extends Parent {

}

private Parent() {

}

}

The inner class InnerChild is an inner class within class Parent. Like any other member within class Parent, the inner class InnerChild can access the private constructor of class Parent. This is quite a common practice where while allowing the benefits of inheritance is also controls what types of objects can be created. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class Box {

public static final class LightBox extends Box { /* ... */ }

public static final class HeavyBox extends Box { /* ... */ }

private Box() { /* ... */ }

}

In the above example, while supports inheritance, we are limiting what kind of boxes can be created. It is not possible for another class to extend the Box class due to the private constructor. We will delve into this aspect later on.

Can a subclass invoke the constructor of a superclass (the super())?

Yes, a subclass can invoke any of the parent’s constructors and pass the required parameters to the parent class. The Box class has two constructors. The following example shows and example of this.

package demo;

import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkArgument;

import static com.google.common.base.Preconditions.checkState;

import static com.google.common.base.Strings.nullToEmpty;

public class LightBox extends Box {

private Space space = Space.AVAILABLE;

public LightBox() {

}

public LightBox( final BoxForm form ) {

super( form );

}

public boolean isEmpty() { /* ... */ }

public void putItem( final long itemId ) { /* ... */ }

@Override

public void changeLabelTo( final String label ) { /* ... */ }

private static boolean isValidLabel( final String label ) { /* ... */ }

private enum Space { /* ... */ }

}

The LightBox now can be initialised open or closed as shown next.

package demo;

import static demo.Box.BoxForm.OPEN;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final LightBox a = new LightBox();

final LightBox b = new LightBox( OPEN );

System.out.printf( "Box a is %s%n", a.isOpen() ? "open" : "closed" );

System.out.printf( "Box b is %s%n", b.isOpen() ? "open" : "closed" );

}

}

The second instance, created an instance of an open box while the first instance creates a closed box.

Box a is closed

Box b is open

A class cannot invoke any of the grandparent’s constructors. Consider the following hierarchy.

The grandparent class,

Apackage demo; public class A { public A() { System.out.println( "A()" ); } public A( int a ) { System.out.printf( "A(int=%d)%n", a ); } }The grandparent has two constructors, the default constructor and another constructor that takes an

int.The parent class,

Bpackage demo; public class B { }The parent class,

B, does not define any constructors and thus a default one is assigned to classB.The child class,

C⚠ The following example does not compile!!package demo; public class C { public C() { super( 10 ); } }Class

C, tries to invoke a constructor that takes anintas its sole parameter. ClassAhas such constructor but classBdoes not.

Can a constructor in a parent class call a method in a subclass?

Yes, but that’s a slippery and dangerous slope. The parent constructor executes before the child’s properties are initialised and the child’s constructor is executed. This means that the child may have not been initialised yet and it may behave in an unexpected manner.

Consider the following parent class

⚠️ NOT RECOMMENDED!!

package demo;

public class Parent {

public Parent() {

aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState();

}

public void aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() {

}

}

The method aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() can be overridden by any child class and access the state. Now consider the following example of a child class.

package demo;

public class Child extends Parent {

private int a = 7;

public void aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() {

System.out.printf( "The value of property a is: %d%n", a );

}

}

This is a trivial class that has a single property named a. The property is also initialised to 7. Given that the aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() is invoked by the Parent’s constructor. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

new Child();

}

}

Surprisingly enough, this will print 0 as shown next.

The value of property a is: 0

The property exists, but it has not yet been initialised. The property is not final for a purpose as this will behave differently.

To help us visualise the problem, let’s add some print outs at each stage.

⚠️ NOT RECOMMENDED!!

package demo;

public class Parent {

{

System.out.println( "Parent::{}" );

}

public Parent() {

System.out.println( "Parent::Parent()" );

aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState();

}

public void aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() {

System.out.println( "Parent::aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState()" );

}

}

Will do the same to the child class.

package demo;

public class Child extends Parent {

private int a = 7;

{

System.out.println( "Child::{}" );

}

public Child() {

System.out.println( "Child::Child()" );

}

public void aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() {

System.out.println( "Child::aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState()" );

System.out.printf( "The value of property a is: %d%n", a );

}

}

Running the same example will print the following.

Parent::{}

Parent::Parent()

Child::aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState()

The value of property a is: 0

Child::{}

Child::Child()

Note that the overridden method aMethodThatMayAccessTheChildState() is invoked before the child’s initialisation block (Child::{}) and the child’s constructor (Child::Child()).

Be mindful when invoking methods from within constructors. Prefer static factory methods over constructors and invoke the setup methods before returning the object.

package demo;

public class PreferStaticFactoryMethods {

public static PreferStaticFactoryMethods create() {

final PreferStaticFactoryMethods a = new PreferStaticFactoryMethods();

a.init();

return a;

}

private PreferStaticFactoryMethods() { /* ... */ }

private void init() { /* ... */ }

}

What happens when not all ‘children’ are ‘parents’?

Consider the square and rectangle shapes. All sides of a square are equals, while in a rectangle, only the opposite sides are equal. We need one property to represent the side (or width) of a square while we need two properties to represent the height and the width of a rectangle.

Consider the following (bad) example of inheritance between the square and the rectangle.

⚠️ NOT RECOMMENDED!!

The

Squareclass, has one property,width.package demo; public class Square { public final int width; public Square( final int width ) { this.width = width; } public int calculatePerimeter() { return width * 4; } public int calculateArea() { return width * width; } }The

Rectangleextends theSquareand adds a new property,height.package demo; public class Rectangle extends Square { public final int height; public Rectangle( final int width, final int height ) { super( width ); this.height = height; } public int calculatePerimeter() { return ( width + height ) * 2; } public int calculateArea() { return width * height; } }

The reasoning behind the above design is that given the rectangle has one more property than the square, we simply extend the square and add the missing property.

This is a bad example of inheritance, because despite the appearances not all rectangles are squares. By definition:

- a rectangle is a quadrilateral with all four angles right angles

- a square is a quadrilateral with all four angles right angles and all four sides of the same length.

In other words, a square is a special type of rectangle. According to the definitions listed above, all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares. Therefore, the inheritance must follow this rule and the square should extend the rectangle and not vice versa.

The above implementation is incorrect. The following example shows a better implementation that captures the above definitions.

The

Rectangleclasspackage demo; public class Rectangle { public final int width; public final int height; public Rectangle( final int width, final int height ) { this.width = width; this.height = height; } public int calculatePerimeter() { return ( width + height ) * 2; } public int calculateArea() { return width * height; } }The

Squareclass, extends theRectangleand exposes only one constructor.package demo; public class Square extends Rectangle { public Square( final int width ) { super( width, width ); } }

This is a typical problem with inheritance where the wrong hierarchy is built. Such hierarchies maybe hard to change at a later stage as other things may be depending on it.

There are many other examples. Cats and dogs are pets but not all pets are cats. If someone asks for cat, we cannot give them a dog. Therefore, when designing such hierarchy, we need to be careful to capture the “all children are parent”, otherwise we may end up with some flawed design.

The Java API has some unfortunate examples of bad inheritance too. The Properties class is a “good” example of bad inheritance. The Properties class inherits from the Hashtable class. The Stack class is another bad example of inheritance within the Java API, The Stack class extends the Vector class and inherits all methods the Vector defined. Some of these methods do not make sense from a stack data structure perspective.

The topic inheritance and composition touches about these problems and propose an alternative approach to inheritance (composition). This topic is also covered in great depths in Item 18: Favor composition over inheritance in the Effective Java.

Is inheritance evil and should be considered as an anti-pattern?

The internet is littered with articles reading “inheritance is evil” and most of them show very bad examples of inheritance. Another common topic that is brought up when discussing inheritance is “inheritance breaks encapsulation”.

Is inheritance evil?

No, inheritance is not evil and nor an anti-pattern. Inheritance is an important part of OOP and has its place. With that said, and like many other things, inheritance can be misused and these articles feast on that. In fact, inheritance can be easily misused especially when the “all children are parent” rule is not followed. Furthermore, inheritance binds classes together, making the class hierarchy brittle. Adding functionality to a parent class, for example, will affect all children and that can be dangerous.

Let’s see an extreme example. Say we have a Shape class, that defines two abstract methods, calculateArea() and calculatePerimeter(). All shapes have an area and perimeter and that’s great. Then we create Circle, Rectangle and other shapes and make them all inherit from the Shape class. Now say we add a new method, called calculateCircumference(), to the Shape class. That would force the rectangular shapes to also have a circumference, which is not the case.

Take for example, serialisation, another Java API which did not withstand the test of time. If the parent class, in a class hierarchy, is made Serializable, then all subclasses will become serializable. This is not something to take lightly as it may have serious consequences. Even Effective Java talks about the issues of serialisation and suggested other approaches in Item 85: Prefer alternatives to Java serialization.