Covariance and invariance

Table of contents

Variance

The Liskov substitution principle (LSP) tells us that any subtype of T can be used when T is required.

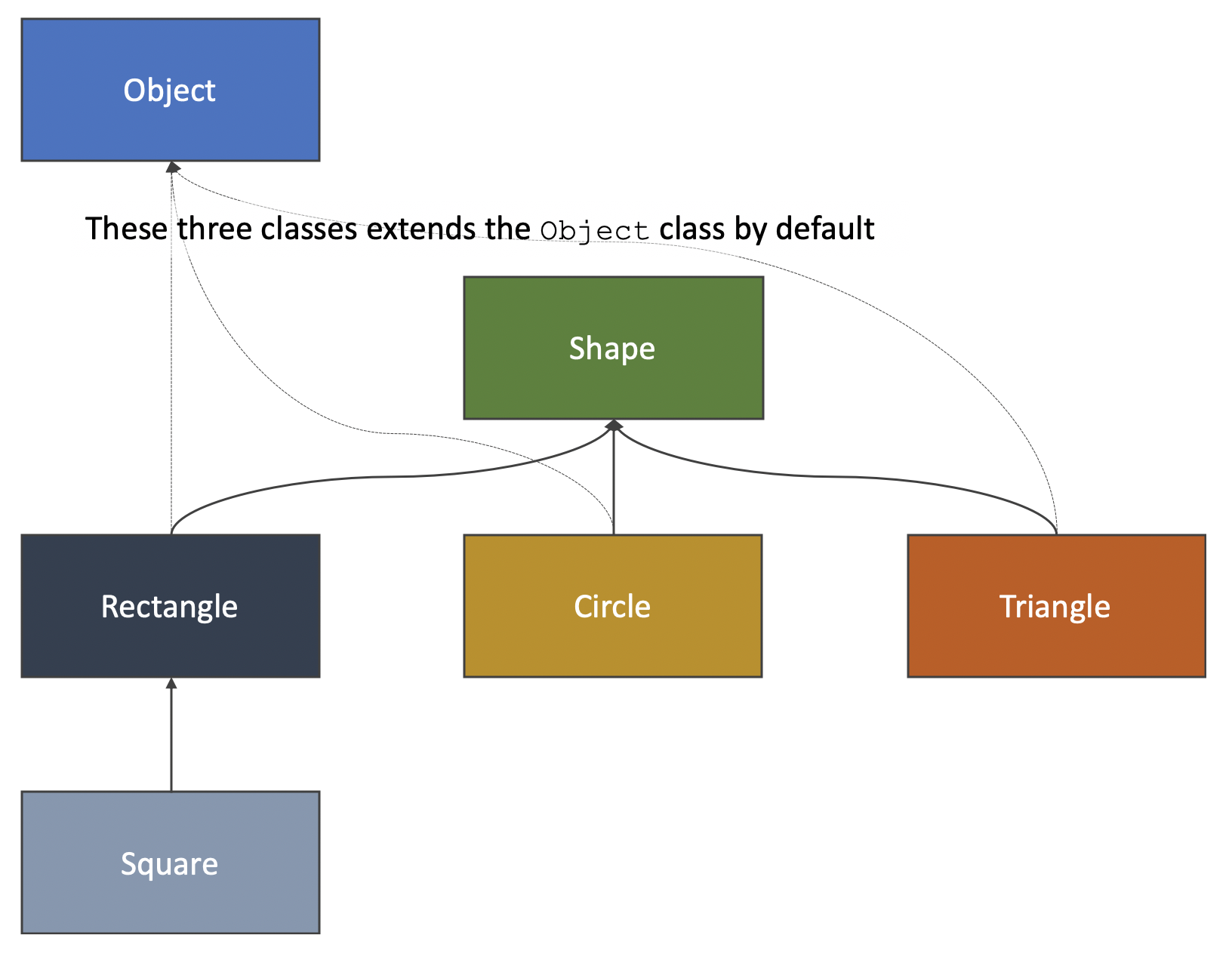

Consider the following classes.

A type,

Shapepackage demo; public interface Shape { double perimeter(); double area(); }A subtype,

Rectanglepackage demo; import lombok.AllArgsConstructor; @AllArgsConstructor public class Rectangle implements Shape { private final double a; private final double b; @Override public double perimeter() { return ( a + b ) * 2; } @Override public double area() { return a * b; } }A subtype,

Squarepackage demo; public class Square extends Rectangle { public Square( final double a ) { super( a, a ); } }A subtype,

Circlepackage demo; import lombok.AllArgsConstructor; @AllArgsConstructor public class Circle implements Shape { private final double d; @Override public double perimeter() { return Math.PI * d; } @Override public double area() { final double r = d / 2; return Math.PI * r * r; } }A subtype,

Trianglepackage demo; import lombok.AllArgsConstructor; @AllArgsConstructor public class Triangle implements Shape { private final double a; private final double b; private final double c; @Override public double perimeter() { return a + b + c; } @Override public double area() { double p = perimeter() / 2; return Math.sqrt( p * ( p - a ) * ( p - b ) * ( p - c ) ); } }

According to the LSP, we can use an instance of Triangle (or Circle or Rectangle or Square), wherever a Shape is required, as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Shape a = new Circle( 7 );

final Shape b = new Square( 4 );

}

}

This applies to collections too. For example an ArrayList implements the List interface, and we can use an instance of ArrayList whenever a List is required, as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Shape>();

}

}

Now consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Shape[] array = new Circle[0];

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

final List<Shape> list = new ArrayList<Circle>();

}

}

Variance defines how subtyping between containers types (collections or generic types), or methods’ types (parameters and return values) relate to subtyping.

There are four types of variance that effect the behaviour of generics.

Each of these is discussed in depth in the following sections.

Invariance

The types Triangle, Circle, Rectangle, and Square are all subtypes of Shape and we can add them to a list of type Shape, as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Shape>();

shapes.add( new Square( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

final Shape shape = shapes.get( 0 );

System.out.printf( "Area is: %.2f%n", shape.area() );

}

}

We can also read from the same list as we did with the shape variable.

Generics are invariant which means that, if S is a subtype of T, then GenericType<S> is not a subtype of GenericType<T> and GenericType<T> is not a supertype of GenericType<S>.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

final List<Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Circle>();

}

}

ArrayList<Circle> is not a subtype of ArrayList<Shape> (or List<Shape>), therefore we cannot use ArrayList<Circle> where List<Shape> is required. The same applies to method parameters. You cannot pass a ArrayList<Circle> to a method that requires a List<Shape>.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Circle> circles = new ArrayList<Circle>();

circles.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

circles.add( new Circle( 4 ) );

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

totalArea( circles );

}

private static double totalArea( final List<Shape> shapes ) {

return shapes

.stream()

.map( Shape::area ) /* calculate the area of each shape in the list */

.reduce( Double::sum ) /* sum all areas calculated before */

.orElse( 0D ); /* return 0 if the list was empty */

}

}

The above is quite annoying as Circle is a Shape and thus the above should work. Before we continue ranting about this, let’s consider a different example using arrays.

ArrayStoreException!! package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Shape[] shapes = new Square[2];

/* ⚠️ This will fail at runtime!! */

shapes[0] = new Circle( 7 );

}

}

Arrays on the other hand are covariant, which means that Circle[] is a subtype of Shape[]. Being so flexible, we have opened ourselves to new set of problems. While compiling, the above example fails at runtime with a ArrayStoreException, as shown next.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayStoreException: demo.Circle

at demo.App.main(App.java:9)

Effective Java talks about this in Item 28: Prefer lists to arrays, whereas the title suggests, it recommends lists over arrays as much as possible to avoid such problems.

Generics are not inflexible and we can still achieve the same degree of flexibility with generics without having to pay the same price as arrays as we will see in Covariance, Contravariance and Bi-variance

Covariance

Generics support covariance without having the pitfalls of arrays. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Circle> circles = new ArrayList<Circle>();

circles.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

circles.add( new Circle( 4 ) );

final double area = totalArea( circles );

System.out.printf( "Total area is: %.2f%n", area );

}

private static double totalArea( final List<? extends Shape> shapes ) {

return shapes

.stream()

.map( Shape::area )

.reduce( Double::sum )

.orElse( 0D );

}

}

The totalArea() takes an instance of List<? extends Shape>. This means that the given list will contain Shape or any subtype of Shape, such as Circle or Square.

This means, if S is a subtype of T, then GenericType<S> is a subtype of GenericType<? extends T>. We can use List<Shape>, List<Circle> or List<Square> where a List<? extends Shape> is required. In this example we are defining an upper bound and saying that the list will contain types that are subtypes of Shape (including Shape). The receiver of the list must have an open lower bound as the list may contain anything that extends Shape (including Shape), as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

totalArea( new ArrayList<Shape>() );

totalArea( new ArrayList<Circle>() );

totalArea( new ArrayList<Rectangle>() );

totalArea( new ArrayList<Square>() );

totalArea( new ArrayList<Triangle>() );

}

private static double totalArea( final List<? extends Shape> shapes ) { /* ... */ }

}

We can pass any list which contains shapes. With that said, we cannot pass any list to the totalArea() method. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

totalArea( new ArrayList<Object>() );

}

private static double totalArea( final List<? extends Shape> shapes ) { /* ... */ }

}

Object is not a subtype Shape, therefore, GenericType<Object> is not a subtype of GenericType<? extends Shape>.

Can we use the covariant type?

YES

Consider a method that returns the shape with the largest area, as shown in the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Comparator;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Optional;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Circle> circles = new ArrayList<Circle>();

circles.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

circles.add( new Circle( 4 ) );

final Circle largest = largest( circles ).orElse( null );

System.out.printf( "The largest circle has an area of %.2f%n", largest.area() );

}

private static <T extends Shape> Optional<T> largest( final List<T> shapes ) {

return shapes

.stream()

.max( Comparator.comparingDouble( Shape::area ) );

}

}

The largest() method will return the shape with the largest area, if the given list is not empty, otherwise it returns an empty optional.

The largest circle has an area of 38,48

The largest() method returned an Optional of type Circle, in the above example, because the type of the provided list is Circle. We can use any type that is a subtype of Shape. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Comparator;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Optional;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Rectangle> rectangles = new ArrayList<Rectangle>();

rectangles.add( new Square( 2 ) );

rectangles.add( new Square( 7 ) );

final Rectangle largest = largest( rectangles ).orElse( null );

System.out.printf( "The largest rectangle has an area of %.2f%n", largest.area() );

}

private static <T extends Shape> Optional<T> largest( final List<T> shapes ) { /* ... */ }

}

In the above example works with the Rectangle type.

The largest rectangle has an area of 49,00

The method largest() can be seen as a function that takes a List<T>, where T is a subtype of Shape, and returns an Optional<T>: f(List<T>) → Optional<T>

Does covariance make generics susceptible to the same problem we saw with arrays before?

No.

Let’s revise our previous example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Shape[] shapes = new Square[2];

/* ⚠️ This will fail at runtime!! */

shapes[0] = new Circle( 7 );

}

}

The issue with covariance happens when we try to add something to the array as we are able to add an different subtype.

/* ⚠️ This will fail at runtime!! */

shapes[0] = new Circle( 7 );

When using the <? extends T>, generics does not allow us to assign values. We can read, but we cannot write. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<? extends Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Circle>();

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

}

}

The above example does not compile as we cannot add anything to the variable shapes (of type List<? extends Shape>).

src/main/java/demo/App.java:12: error: incompatible types: Circle cannot be converted to CAP#1

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

^

where CAP#1 is a fresh type-variable:

CAP#1 extends Shape from capture of ? extends Shape

This is very convenient as while the totalArea() method can iterate the given list, it cannot add values to it.

Can a generic type implement two or more interfaces?

Yes

Consider the following classes

An interface

package demo; public interface HasName { String getName(); }Another interface

package demo; import java.math.BigDecimal; public interface HasPrice { BigDecimal getPrice(); }A class that implements these two interfaces

package demo; import lombok.AllArgsConstructor; import lombok.Data; import java.math.BigDecimal; @Data @AllArgsConstructor public class LineItem implements HasName, HasPrice { private final String name; private final BigDecimal price; }

We can define a type that needs to extend both the HasName and HasPrice interfaces as shown in the following example.

package demo;

import java.math.BigDecimal;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

print( new LineItem( "Foldable Bicycle", new BigDecimal( "395.00" ) ) );

}

private static <T extends HasName & HasPrice> void print( final T t ) {

System.out.printf( "%s costs %.2f€%n", t.getName(), t.getPrice() );

}

}

The print() method can take anything that implement both interfaces, such as the LineItem. Furthermore, given that the generic type T implements both interfaces, we are able to invoke the methods defined by the interfaces, such as getName() and getPrice().

Contravariance

We can use generics to control what we can add and cannot add to a collection. Using covariance we can read from a list, but we cannot add items to the list. Using contravariance we can achieve the opposite: we are able add to the list, but we are not expected to read items from the list (at least in the type we expect these items to be). Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<? super Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Shape>();

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Square( 4 ) );

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

final Shape firstShape = shapes.get( 0 );

}

}

While we can add shapes to the list, we cannot read a Shape from the list despite the fact that this is of type Shape.

src/main/java/demo/App.java:14: error: incompatible types: CAP#1 cannot be converted to Shape

final Shape firstShape = shapes.get( 0 );

^

where CAP#1 is a fresh type-variable:

CAP#1 extends Object super: Shape from capture of ? super Shape

Contravariance focus on consumption. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Object> shapes = new ArrayList<Object>();

populate( shapes );

}

public static void populate( List<? super Shape> shapes ) {

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Square( 4 ) );

}

}

The populate() method accepts any list that can contain shapes. A list of objects can contain shapes, thus it is accepted. A list of rectangles, on the other hand, does not accept any shape, only rectangles, thus not accepted, as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

/* ⚠️ This will not compile!! */

populate( new ArrayList<Rectangle>() );

}

public static void populate( List<? super Shape> shapes ) {

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Square( 4 ) );

}

}

The above example is not providing a list that can contain the required type and will fail to compile as shown next.

src/main/java/demo/App.java:9: error: incompatible types: ArrayList<Rectangle> cannot be converted to List<? super Shape>

populate( new ArrayList<Rectangle>() );

^

This may be quite counterintuitive. If S is a subtype of T, then GenericType<T> is a subtype of GenericType<? super S>. In our example, ArrayList<Object> is a subtype of List<? super Shape>, despite from the fact that Shape is subtype of Object.

In Java everything is an Object, which means we can read from the variable shapes. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<? super Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Shape>();

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Square( 4 ) );

final Object firstShape = shapes.get( 0 );

}

}

Alternatively, we can use the var keyword which will achieve the same result.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<? super Shape> shapes = new ArrayList<Shape>();

shapes.add( new Circle( 7 ) );

shapes.add( new Square( 4 ) );

final var firstShape = shapes.get( 0 );

}

}

Bi-variance

There are cases where we need to operate on a collection (generic type) without interacting with its content. Say we need to write a function that verifies whether the ith element in a collection is not null. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<String> names = List.of( "Jade", "Aden" );

final List<Shape> shapes = List.of( new Circle( 7 ), new Square( 4 ) );

isSet( names, 3 );

isSet( shapes, 1 );

}

public static boolean isValueSet( final List<?> list, final int index ) {

return index < list.size() && list.get( index ) != null;

}

}

The isValueSet() method takes a list of any type, List<?>. This is bi-variant, as it has no upper or lower bounds. The list can be of any type. This is ideal when we need to operate on the collection itself, irrespective from the content type.

Examples

Sorting a collection

Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<String> name = new ArrayList<>();

name.add( "Mary" );

name.add( "James" );

Collections.sort( name );

name.forEach( System.out::println );

}

}

The names are sorted alphabetically using the Collections.sort() method.

James

Mary

The Collections.sort() method makes use of generics as shown next.

public class Collections {

public static <T extends Comparable<? super T>> void sort(List<T> list) { /* ... */ }

}

The list needs to be of a type T, that extends Comparable of a supertype of T.

What does this mean?

This may be a bit cryptic. Consider the following Person class.

package demo;

import lombok.AllArgsConstructor;

import lombok.Data;

import org.apache.commons.lang3.StringUtils;

@Data

@AllArgsConstructor

public class Person implements Comparable<Person> {

private final String name;

@Override

public int compareTo( final Person that ) {

return StringUtils.compareIgnoreCase( this.name, that.name );

}

}

The Person class implements Comparable of type Person (implements Comparable<Person>). Now consider the Employee class that extends the Person class, shown next.

package demo;

import lombok.Data;

import lombok.EqualsAndHashCode;

import lombok.ToString;

@Data

@EqualsAndHashCode( callSuper = false )

@ToString( callSuper = true, includeFieldNames = true )

public class Employee extends Person {

private final String employeeNumber;

public Employee( final String name, final String employeeNumber ) {

super( name );

this.employeeNumber = employeeNumber;

}

}

The Employee class extends Person but does not implement Comparable. The Employee class is a Person and also is a Comparable<Person>.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Employee a = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );

final Person b = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );

final Comparable<Person> c = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );

final Object d = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );

}

}

Each assignment is explained next.

An

Employeeis anEmployeefinal Employee a = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );An

Employeeis anPerson, asEmployeeinherits fromPersonfinal Person b = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );An

Employeeis aComparable<Person>transitively.Employeeinherits fromPerson, which in turn implementsComparable<Person>final Comparable<Person> c = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );Everything in Java is an

Objectfinal Object d = new Employee( "Albert", "JVM-0110" );

We can sort a list of employees, because the Employee (T) implements a Comparable of its supertype, Person, (Comparable<? super T>). Following is an example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.List;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final List<Employee> employees = new ArrayList<>();

employees.add( new Employee( "Mary", "ENG-0700" ) );

employees.add( new Employee( "James", "MNG-0906" ) );

Collections.sort( employees );

employees.forEach( System.out::println );

}

}

The employees are sorted using the Person’s comparator as shown next.

Employee(super=Person(name=James), employeeNumber=MNG-0906)

Employee(super=Person(name=Mary), employeeNumber=ENG-0700)