Top-level, inner and anonymous classes

Table of contents

- Top level class

- Inner instance class

- Inner static class

- Inner anonymous class

- Local class

- JEP 360: Sealed Classes (Preview)

- What is effectively final variables?

Top level class

Top level classes are class declarations at the top-level of the source file. A source file can have one, or more, top-level classes, as shown next.

package demo;

public class TopLevelClass {

}

class AnotherTopLevelClass {

}

The above source file, src/main/java/demo/TopLevelClass.java, has two top-level classes. Note that there can be only one public top-level class within one source file and that top-level class must have the same name as the source file, TopLevelClass in our example.

Having multiple top-level classes in one source file adds little advantages and is it not a recommended practice. Effective Java talks about this too in Item 25: Limit source files to a single top-level class.

Inner instance class

An inner instance class is a class within a class. Different from a top-level class, an inner class is another class member, like a method is for example. The following example shows a very simple example of an inner instance class.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerClass {

public class AnInnerClass {

}

}

An inner instance class can access the state of the enclosing class like any other instance method as shown in the following example.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerClass {

private final int a = 7;

public class AnInnerClass {

public void printValue() {

System.out.printf( "The value of a is %d%n", a );

}

}

}

Inner classes, in general, are great to represent data in a different form or to simplify internal data handling.

How can inner instance classes represent data in a different form?

Let say that we have a matrix of integers.

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

├───┼───┼───┼───┼───┤

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

├───┼───┼───┼───┼───┤

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

The above matrix can be representing as a two-dimensional array of int (int[][]), as shown next.

package demo;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) {

this. matrix = matrix;

}

}

Now say that we need to get the data as rows, where each row is represented as an int[], as shown next. How can we do that?

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

┌───┬───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │ 5 │

└───┴───┴───┴───┴───┘

Furthermore, how can we represent the data as columns instead, where each column is represented as an int[]?

┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐ ┌───┐

│ 1 │ │ 2 │ │ 3 │ │ 4 │ │ 5 │

├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤

│ 1 │ │ 2 │ │ 3 │ │ 4 │ │ 5 │

├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤ ├───┤

│ 1 │ │ 2 │ │ 3 │ │ 4 │ │ 5 │

└───┘ └───┘ └───┘ └───┘ └───┘

We can represent the data in different forms using inner instance classes as shown next.

Note that the following example make use of matrix transposition and Java streams. Do not worry if you do not understand these. These were added to the example to make it more meaningful.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) {

this. matrix = matrix;

}

public Iterable<int[]> rows() {

return new Rows();

}

public Iterable<int[]> columns() {

return new Columns();

}

private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> {

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( matrix )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

}

private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> {

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( transposed() )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

private int[][] transposed() {

final int m = matrix.length;

final int n = matrix[0].length;

final int[][] transposed = new int[n][m];

for ( int x = 0; x < n; x++ ) {

for ( int y = 0; y < m; y++ ) {

transposed[x][y] = matrix[y][x];

}

}

return transposed;

}

}

}

Both the Rows and Columns inner instance classes implement the Iterable of type int[] interface. Any type that implements the Iterable interface, can be used within the for-each loop as shown in the following fragment.

final Data data = ...;

for ( final int[] row : data.rows() ) { /* ... */ }

Let’s break the Data class into smaller parts.

Rowspackage demo; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.Iterator; import java.util.stream.Collectors; public class Data { private final int[][] matrix; public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ } public Iterable<int[]> rows() { return new Rows(); } public Iterable<int[]> columns() { /* ... */ } private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> { @Override public Iterator<int[]> iterator() { return Arrays.stream( matrix ) .collect( Collectors.toList() ) .iterator(); } } private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ } }Rowsis an inner instance class that represents anIterableof typeint[]. It takes thematrixand creates a list with each row as the list elements and then takes advantage of theList.iterator().As mentioned before, do not worry about the implementation details here as these may be beyond our pay grade. The most important thing is that, using inner classes we are able to navigate the data in a different manner, rows in this case.

Columnspackage demo; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.Iterator; import java.util.stream.Collectors; public class Data { private final int[][] matrix; public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ } public Iterable<int[]> rows() { /* ... */ } public Iterable<int[]> columns() { return new Columns(); } private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ } private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> { @Override public Iterator<int[]> iterator() { return Arrays.stream( transposed() ) .collect( Collectors.toList() ) .iterator(); } private int[][] transposed() { /* ... */ } } }Columnsis almost identical toRowswith one small difference, it makes use of the transposed version of the matrix as we want to return the columns instead of the rows. So first we rotate the matrix by 90 degrees and then use the same technique we used when creating theRows.

Both the Rows and Columns instance classes make use of the matrix property defined in the enclosing class, Data. This is an advantage of inner instance classes. We don’t have to pass any values. With that said this comes with a downside as we will see in a bit.

Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final int[][] matrix = {

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 },

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 },

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }

};

final Data data = new Data( matrix );

System.out.println( "-- Rows view of the data -----" );

for ( final int[] row : data.rows() ) {

System.out.printf( "%s%n", Arrays.toString( row ) );

}

System.out.println( "-- Columns view of the data --" );

for ( final int[] column : data.columns() ) {

System.out.printf( "%s%n", Arrays.toString( column ) );

}

}

}

The above example shows how we can easily work with rows or columns as required.

-- Rows view of the data -----

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

-- Columns view of the data --

[1, 1, 1]

[2, 2, 2]

[3, 3, 3]

[4, 4, 4]

[5, 5, 5]

Note that both the Rows and Columns are declared as private, and these types are never returned. Instead we return the Iterable<int[]> from the rows() and columns() methods. Our example did not require anything else more than what is provided by the Iterable<int[]> interface. Always start with the least possible visibility and open up only when needed. We can always refactor this and return something more specific when this is needed.

The use of inner instance classes to represent the data in different forms is very common and used a lot within the Java collections. The following code fragment shows how the ArrayList makes use of this technique to return an Iterator<E> by its iterator() method using the inner instance class named Itr.

package java.util;

public class ArrayList<E> extends AbstractList<E> implements List<E>, RandomAccess, Cloneable, Serializable {

public Iterator<E> iterator() {

return new Itr();

}

private class Itr implements Iterator<E> { /* ... */ }

}

As in our example the Itr is private and never exposed to the outside word.

Internal types

Another use of inner instance classes is to represent a type internally. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class Pairs {

private final List<Pair> pairs = new ArrayList<>();

public void add( final int a, final int b ) {

pairs.add( new Pair( a, b ) );

}

private class Pair {

final int a;

final int b;

private Pair( final int a, final int b ) {

this.a = a;

this.b = b;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "(%d,%d)", a, b );

}

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return pairs.toString();

}

}

The Pairs class takes pairs of ints and collects them in a list a shown in the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Pairs pairs = new Pairs();

pairs.add( 1, 2 );

pairs.add( 3, 4 );

pairs.add( 5, 6 );

System.out.printf( "Pairs: %s%n", pairs );

}

}

The above will print the following.

Pairs: [(1,2), (3,4), (5,6)]

Let’s turn back to the Pairs class. The Pairs class has an inner instance class which groups the provided ints.

package demo;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class Pairs {

private final List<Pair> pairs = new ArrayList<>();

public void add( final int a, final int b ) {

pairs.add( new Pair( a, b ) );

}

private class Pair { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() { /* ... */ }

}

This is quite a common practice where a class will use internal types, like our Pair inner instance class, to represent that data internally. Note that in the above example the Pair is private and never used outside the enclosing class. The main purpose of this inner instance class is simply to help the enclosing class organising its data.

Why is the use of inner instance class discouraged?

Inner instance classes have a reference to the object from where these where created. This is not seen in the code. We were able to access the parent’s object state without had to think about it.

With reference to the Data class mentioned before.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] table;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> rows() { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> columns() { /* ... */ }

private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ }

private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ }

}

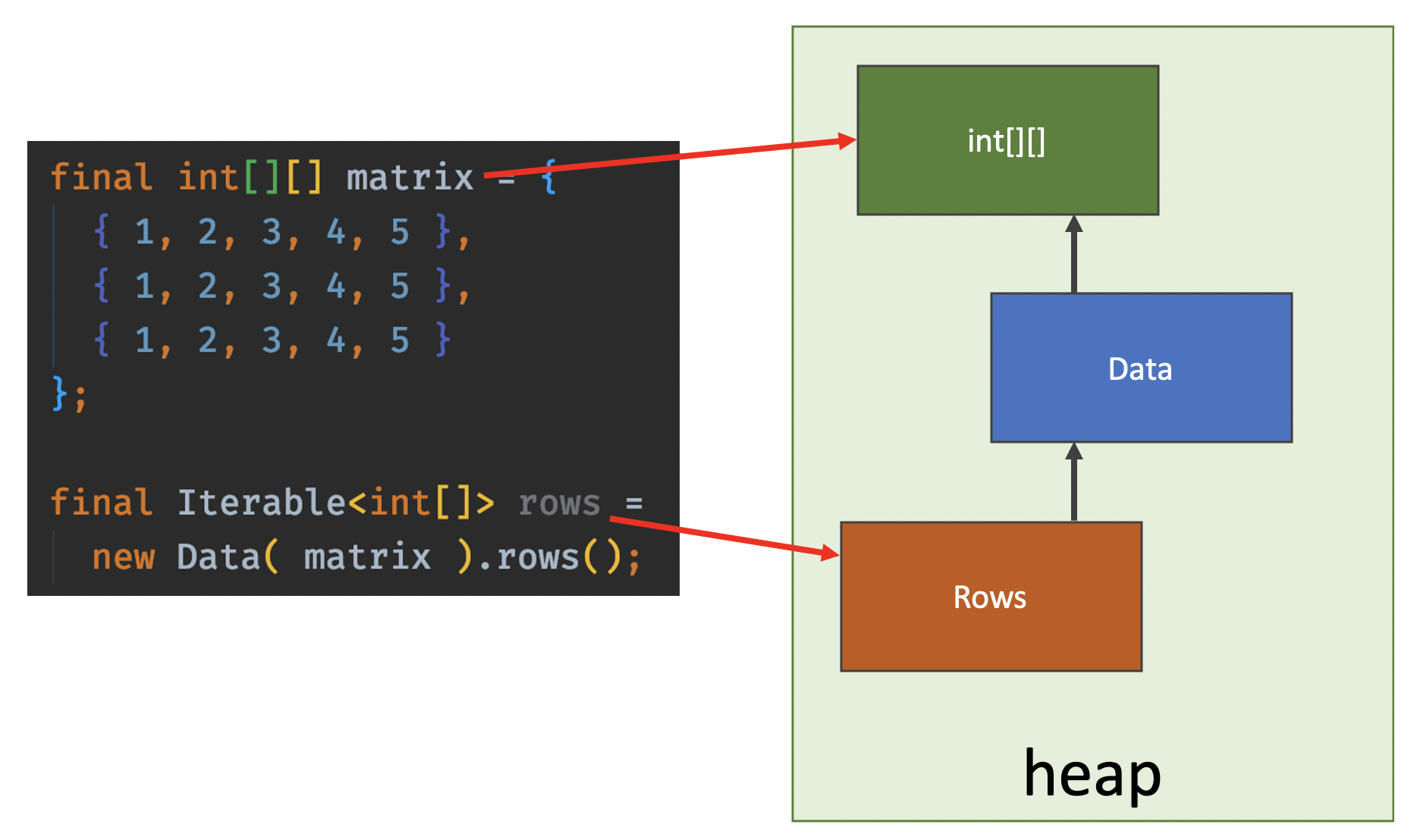

Now consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final int[][] matrix = {

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 },

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 },

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }

};

final Iterable<int[]> rows = new Data( matrix ).rows();

}

}

In the above example, we create an instance of Data and then simply return the rows, by invoking the rows() method. The instance of Data, created by the new Data(), is never saved in a variable and therefore we have no variables pointing to this object in the heap as shown next.

Some programmers will mistakenly think that the data object will be garbage collected as we are not referring to it. After all, there is no reference to the Data class from within the Rows inner class, shown next.

private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> {

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( matrix )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

}

The Rows class shown next has no state after all. Appearances cannot be more deceiving.

The Rows class has a reference to the parent class even though it is not visible. Let’s see the Rows’ class bytecode (View > Show Bytecode).

// class version 58.65535 (-65478)

// access flags 0x20

// signature Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/Iterable<[I>;

// declaration: demo/Data$Rows implements java.lang.Iterable<int[]>

class demo/Data$Rows implements java/lang/Iterable {

// compiled from: Data.java

NESTHOST demo/Data

// access flags 0x2

private INNERCLASS demo/Data$Rows demo/Data Rows

// access flags 0x1010

final synthetic Ldemo/Data; this$0

// access flags 0x2

private <init>(Ldemo/Data;)V

L0

LINENUMBER 23 L0

ALOAD 0

ALOAD 1

PUTFIELD demo/Data$Rows.this$0 : Ldemo/Data;

ALOAD 0

INVOKESPECIAL java/lang/Object.<init> ()V

RETURN

L1

LOCALVARIABLE this Ldemo/Data$Rows; L0 L1 0

MAXSTACK = 2

MAXLOCALS = 2

// access flags 0x1

// signature ()Ljava/util/Iterator<[I>;

// declaration: java.util.Iterator<int[]> iterator()

public iterator()Ljava/util/Iterator;

L0

LINENUMBER 26 L0

ALOAD 0

GETFIELD demo/Data$Rows.this$0 : Ldemo/Data;

GETFIELD demo/Data.table : [[I

INVOKESTATIC java/util/Arrays.stream ([Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/util/stream/Stream;

L1

LINENUMBER 27 L1

INVOKESTATIC java/util/stream/Collectors.toList ()Ljava/util/stream/Collector;

INVOKEINTERFACE java/util/stream/Stream.collect (Ljava/util/stream/Collector;)Ljava/lang/Object; (itf)

CHECKCAST java/util/List

L2

LINENUMBER 28 L2

INVOKEINTERFACE java/util/List.iterator ()Ljava/util/Iterator; (itf)

L3

LINENUMBER 26 L3

ARETURN

L4

LOCALVARIABLE this Ldemo/Data$Rows; L0 L4 0

MAXSTACK = 2

MAXLOCALS = 1

}

We don’t need to understand the whole this. Let’s instead just focus on the parts relevant to us.

The bytecode of the

Rowsclass shows that theRowsclass actually has a property of typedemo.Dataas shown in the following fragment.// access flags 0x1010 final synthetic Ldemo/Data; this$0The bytecode also indicates that we have a constructor that takes an instance of

demo.Dataas shown in the following fragment.// access flags 0x2 private <init>(Ldemo/Data;)V L0 LINENUMBER 23 L0 ALOAD 0

When compiling an inner instance class, the Java compiler adds a parameter of the enclosing class type, Data in our case, as the first parameter to each constructor, and the default constructor is not an exception.

Effective Java dives into this too in Item 24: Favor static member classes over nonstatic

Can we have static methods within inner instance classes?

No. Inner instance classes, like inner anonymous classes, cannot have static members.

Can we create an instance of an inner instance class from outside the enclosing class?

Yes, but I never saw this used anywhere apart from books and the syntax looks weird. Consider the following class that also contains an inner instance class.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerClass {

private final int a = 7;

public class AnInnerClass {

public void printValue() {

System.out.printf( "The value of a is %d%n", a );

}

}

}

We can create an instance of the inner class, AnInnerClass, from outside the enclosing class, as shown in the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final ClassWithAnInnerClass a = new ClassWithAnInnerClass();

final ClassWithAnInnerClass.AnInnerClass b = a.new AnInnerClass();

b.printValue();

}

}

Note that an inner instance class needs to be linked to an object of its enclosing class. That is why we need to create the inner instance class through the variable of the enclosing class, ClassWithAnInnerClass in our case.

a.new AnInnerClass()

I would avoid this and instead I would use a method within the enclosing class that will return an instance of the inner class, as shown next.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerClass {

private final int a = 7;

public AnInnerClass newInnerClass() {

return new AnInnerClass();

}

public class AnInnerClass {

private AnInnerClass() { }

public void printValue() { /* ... */ }

}

}

Note that the constructor of the inner instance class, AnInnerClass, is private to prevent it from being initialised from outside the enclosing class. We cannot create an instance of AnInnerClass from the App class as we did in the the other example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final ClassWithAnInnerClass a = new ClassWithAnInnerClass();

final ClassWithAnInnerClass.AnInnerClass b = a.newInnerClass();

b.printValue();

}

}

The above example reads better as it uses a code style that every is accustom to.

Inner static class

An inner static class is a class within a class which is marked as static. Different from a top-level class, an inner static class is another class member, like a static method is for example. The following example shows a very simple example of an inner static class.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerStaticClass {

public static class AnInnerStaticClass {

}

}

An inner static class cannot access the state of the enclosing class. These behave similar to static methods within the same class.

package demo;

public class ClassWithAnInnerStaticClass {

private static int A = 7;

public static class AnInnerStaticClass {

public static void printValue() {

System.out.printf( "The value of the static field A is %d%n", A );

}

}

}

What’s the difference between inner instance classes and inner static classes?

Difference for inner instance classes, an inner static class is not automatically linked to the enclosing object. Therefore, an inner static class, cannot access the state of the enclosing object as the inner instance class does.

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class ClassWithInnerClasses {

private final int a = 7;

public class InnerClass {

public void printValue() {

System.out.printf( "The value of the property a is %d%n", a );

}

}

public static class InnerStaticClass {

public void printValue() {

/* ⚠️ cannot access instance properties of the enclosing class */

System.out.printf( "The value of the property a is %d%n", a );

}

}

}

As mentioned in an earlier section, titled why is the use of inner instance class discouraged?, the inner instance class is provided a reference to the enclosing object automatically by the compiler. We can refactor the inner static class and pass an instance of the enclosing object to it, as shown next.

package demo;

public class ClassWithInnerClasses {

private final int a = 7;

public class InnerClass { /* ... */ }

public static class InnerStaticClass {

private final ClassWithInnerClasses enclosingObject;

private InnerStaticClass( final ClassWithInnerClasses enclosingObject ) {

this.enclosingObject = enclosingObject;

}

public void printValue() {

System.out.printf( "The value of the property a is %d%n", enclosingObject.a );

}

}

}

Inner static classes can be seen as a super set of the inner instance classes as they can also have static members. We can convert all inner instance classes with inner static classes, but not vice versa as inner instance classes cannot have static members as discussed before, while inner static class do.

We can refactor the Data class, shown before when we discussed how can inner instance classes represent data in a different form?, to make use of inner static class instead.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) {

this. matrix = matrix;

}

public Iterable<int[]> rows() {

return new Rows();

}

public Iterable<int[]> columns() {

return new Columns();

}

private class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> {

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( matrix )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

}

private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> {

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( transposed() )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

private int[][] transposed() {

final int m = matrix.length;

final int n = matrix[0].length;

final int[][] transposed = new int[n][m];

for ( int x = 0; x < n; x++ ) {

for ( int y = 0; y < m; y++ ) {

transposed[x][y] = matrix[y][x];

}

}

return transposed;

}

}

}

Let’s start with the simplest class, Rows.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> rows() {

return new Rows( matrix );

}

public Iterable<int[]> columns() { /* ... */ }

private static class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> {

private final int[][] matrix;

private Rows( final int[][] matrix ) {

this.matrix = matrix;

}

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( matrix )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

}

private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ }

}

Now, when initialising the Rows, we need to pass an instance of the matrix.

return new Rows( matrix );

Note that here we are not passing an instance of Data, but an instance of the two-dimensional array instead. This means that the Rows does not have a reference to the enclosing object.

We can refactor the Columns too.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> rows() { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> columns() {

return new Columns( matrix );

}

private static class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> { /* ... */ }

private class Columns implements Iterable<int[]> {

private final int[][] matrix;

private Columns( final int[][] matrix ) {

this.matrix = matrix;

}

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( transposed() )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

private int[][] transposed() {

final int m = matrix.length;

final int n = matrix[0].length;

final int[][] transposed = new int[n][m];

for ( int x = 0; x < n; x++ ) {

for ( int y = 0; y < m; y++ ) {

transposed[x][y] = matrix[y][x];

}

}

return transposed;

}

}

}

Note that the Rows and Columns are quite similar and can be consolidated as one inner static class, as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Iterator;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Data {

private final int[][] matrix;

public Data( final int[][] matrix ) { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> rows() { /* ... */ }

public Iterable<int[]> columns() {

return new Rows( transposed() );

}

private int[][] transposed() {

final int m = matrix.length;

final int n = matrix[0].length;

final int[][] transposedMatrix = new int[n][m];

for ( int x = 0; x < n; x++ ) {

for ( int y = 0; y < m; y++ ) {

transposedMatrix[x][y] = matrix[y][x];

}

}

return transposedMatrix;

}

private static class Rows implements Iterable<int[]> {

private final int[][] matrix;

private Rows( final int[][] matrix ) {

this.matrix = matrix;

}

@Override

public Iterator<int[]> iterator() {

return Arrays.stream( matrix )

.collect( Collectors.toList() )

.iterator();

}

}

}

Not exposing the Rows and Columns inner static class, enable us to drop one of the inner static classes, without having to worry about other external usage. All external usage, relied on the Iterable<int[]> interface instead.

Inner anonymous class

Consider the following method.

private static void runMyJob( final Runnable runnable ) {

runnable.run();

}

We can pass anything to this method that implements the Runnable interface. Consider the following class.

package demo;

public class SimpleJob implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println( "My simple job" );

}

}

We can pass an instance of SimpleJob, as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

runMyJob( new SimpleJob() );

}

private static void runMyJob( final Runnable runnable ) {

runnable.run();

}

}

Instead, we can replace the SimpleJob with an inner anonymous class as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

runMyJob( new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println( "My simple job" );

}

} );

}

private static void runMyJob( final Runnable runnable ) {

runnable.run();

}

}

When the interface in question is a functional interface, we can replace the inner anonymous class with a lambda function as shown next.

runMyJob( () -> System.out.println( "My simple job" ) );

What are the differences between lambda functions and inner anonymous classes (revised)?

In some cases, lambda functions and inner anonymous classes can be used interchangeably. With reference to the example shown before, the Runnable interface is a functional interface, thus can be replaced by a lambda function. Lambda cannot be used to replace classes or interfaces that have more than one abstract method (non-functional interface).

Consider the following three classes.

A functional interface that represents a worker

package demo; public interface Worker { void work(); }A functional interface that represents a task

package demo; public interface Task { void execute(); }An application that uses these two interfaces

package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { /* Nothing is happening yet */ } private static void execute( final Worker worker ) { worker.work(); } private static void execute( final Task task ) { task.execute(); } }

Following are some key differences between lambda functions and inner anonymous class, in the above context.

Inner anonymous classes are typed and will only fit one type. We can create an inner anonymous class for either

WorkerorTask, but not for both. One inner anonymous class cannot extend or implement two or more types.package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { execute( new Worker() { @Override public void work() { System.out.println( "My worker" ); } } ); } private static void execute( final Worker worker ) { worker.work(); } private static void execute( final Task task ) { task.execute(); } }Given that the inner anonymous class is typed, the

execute()method that takes aWorkeris invoked. On the contrary, lambda functions are not typed as we cannot simply replaced the above with a lambda function, as shown next.⚠ The following example does not compile!!package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { /* ⚠️ Both execute() methods will match!! */ execute( () -> System.out.println( "My worker" ) ); } private static void execute( final Worker worker ) { worker.work(); } private static void execute( final Task task ) { task.execute(); } }We can address the above issue by casting the lambda function to an interface of type

Worker, as shown next.execute( (Worker) () -> System.out.println( "My worker" ) );Alternatively, we can cast type the lambda function to a

Task, as shown next.execute( (Task) () -> System.out.println( "My task" ) );We can cast type a lambda function to any functional interface.

The inner anonymous class are bound to a class file, while lambda functions are not bound to a class file.

Consider the following example

package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { execute( (Worker) () -> System.out.println( "My worker" ) ); execute( new Task() { @Override public void execute() { System.out.println( "My task" ); } } ); } private static void execute( final Worker worker ) { worker.work(); } private static void execute( final Task task ) { task.execute(); } }In the above example, we have an inner anonymous class and a lambda function.

We have three source files, as shown next.

$ tree src/main/java src/main/java └── demo ├── App.java ├── Task.java └── Worker.javaClean and then build the project to remove any residual from any previous builds.

$ ./gradlew clean buildThe

cleanGradle task will delete any previously generated classes. List all generated classes.$ tree build/classes/java build/classes/java └── main └── demo ├── App$1.class ├── App.class ├── Task.class └── Worker.classNote that here we have a class file,

Task.classandWorker.class, for each interface,TaskandWorker. We have theApp.classclass file and another class file for the inner anonymous class,App$1.class. We have no class files for the lambda function.Lambda functions are not bound to a class file. Java creates a class, also referred to as runtime classes, when the lambda function is first invoked. In Java, you cannot escape classes, as classes in Java are the smallest unit of work.

Inner anonymous classes have access to

thisandsuperlike any other class. Lambda functions on the other hand do not have access tothisorsuper.“Unlike code appearing in anonymous class declarations, the meaning of names and the

thisandsuperkeywords appearing in a lambda body, along with the accessibility of referenced declarations, are the same as in the surrounding context (except that lambda parameters introduce new names).“

(JLS 15.27.2)While lambda functions are bound to functional interfaces, inner anonymous classes can extend or implements any class or interface on the fly. Inner anonymous classes are not bound to just functional interfaces. Instead we can use inner anonymous classes with anything that can be extended.

Note that while we can use inner anonymous classes with classes too, we cannot create an inner anonymous class of a final class.

How many methods can an inner anonymous class override?

An inner anonymous class can override as many methods it needs. An inner anonymous class is very similar to an inner instance class and as such, an inner anonymous class cannot have static members.

Consider the following example.

public interface Pet {

String getName();

String getFavouriteFood();

}

The above Pet interface has two abstract methods. As shown in the following example, we can create an inner anonymous class and override two abstract methods.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Pet pet = new Pet() {

@Override

public String getName() {

return "Fido";

}

@Override

public String getFavouriteFood() {

return "Sausage pizza";

}

};

System.out.printf( "My pet's name is %s, and it likes %s%n", pet.getName(), pet.getFavouriteFood() );

}

}

The above example will print.

My pet's name is Fido, and it likes Sausage pizza

We can override any method that can be overridden using an inner anonymous class. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Pet pet = new Pet() {

@Override

public String getName() { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String getFavouriteFood() { /* ... */ }

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "My pet's name is %s and it likes %s%n", getName(), getFavouriteFood() );

}

};

System.out.println( pet );

}

}

The above example shows how an inner anonymous class overrides concrete methods such as the toString() method.

Can we add methods to an inner anonymous class?

Yes, inner anonymous classes can have other instance methods, and not just those inherited from the class it is extending or the interface it is implementing.

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Object a = new Object() {

public void sayHello( final String name ) {

System.out.printf( "Hello %s%n", name );

}

};

/* ⚠️ The object class does not have a sayHello() method!! */

a.sayHello( "Jade" );

}

}

The above example will not compile as the Object class has no method called sayHello(). Inner anonymous classes do not define a new type and thus we cannot create a variable of type of the inner anonymous class.

Java 10, introduced JEP 286: Local-Variable Type Inference which changed the whole game.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final var a = new Object() {

public void sayHello( final String name ) {

System.out.printf( "Hello %s%n", name );

}

};

a.sayHello( "Jade" );

}

}

Using the var keyword, Java will determine the type by looking at the right-hand side of the assignment operator. The above now compiles and will print.

Hello Jade

Inner anonymous classes can be used within streams as we will see next. Consider the following class.

package demo;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final int age;

public Person( final String name, final int age ) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

}

Now let say that we would like to print the age of a person in dog years. For the sake of this example, let us assume that 15 dog years is 1 human year. Consider the following, overly complicated, example.

package demo;

import java.util.stream.Stream;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

Stream.of(

new Person( "Aden", 16 ),

new Person( "Jade", 32 ),

new Person( "Mary", 57 ),

new Person( "Peter", 92 )

).map( person -> new Object() {

final String name = person.getName();

public int getDogAge() {

/* 15 human years equals the first year of a medium-sized dog's life */

return person.getAge() / 15;

}

}

).forEach( a -> {

System.out.printf( "%s would be %d years old%n", a.name, a.getDogAge() );

} );

}

}

Here we have a stream of persons, is then mapped to an inner anonymous class. The inner anonymous class adds a new property, name and a new instance method, getDogAge(). This new method can be then invoked as we saw in the foreach termination part of the stream.

Aden would be 1 years old

Jade would be 2 years old

Mary would be 3 years old

Peter would be 6 years old

While yes, we can have new methods within an inner anonymous class, I recommend keeping the inner anonymous classes as small as possible. Once an inner anonymous class starts to get big, then it starts losing its benefit, and it is best to convert it to an inner anonymous type or move it to a separate class. The latter will make it testable.

Local class

Strangely enough, we can create a class within a method, initialisation blocks or constructors, as shown in the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

class Person {

private final String name;

private final int age;

public Person( final String name, final int age ) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, age=%d}", name, age );

}

}

final Person a = new Person( "Aden", 11 );

final Person b = new Person( "Jade", 13 );

System.out.println( a );

System.out.println( b );

}

}

The main() method has defined a local class named Person;

Person{name=Aden, age=11}

Person{name=Jade, age=13}

The new local class, Person is only available within the method. Similar to other types of inner classes, the local class is bound to a class file. We only have one source file in our application as shown next.

$ tree src/main/java

src/main/java

└── demo

└── App.java

Build the application to produce all class files.

$ ./gradlew clean build

Note that we have two class files.

$ tree build/classes/java

build/classes/java

└── main

└── demo

├── App$1Person.class

└── App.class

The App$1Person.class class file represents the local class.

Local classes can be defined within inner scopes such as an if statement block, as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Random random = new Random();

final boolean hasNameAndAge = random.nextBoolean();

if ( hasNameAndAge ) {

class Person {

private final String name;

private final int age;

public Person( final String name, final int age ) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

@Override public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, age=%d}", name, age );

}

}

final Person a = new Person( "Aden", 11 );

final Person b = new Person( "Jade", 13 );

System.out.println( a );

System.out.println( b );

} else {

class Person {

private final String name;

public Person( final String name ) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s}", name );

}

}

final Person a = new Person( "Aden" );

final Person b = new Person( "Jade" );

System.out.println( a );

System.out.println( b );

}

}

}

The above example is an extreme example. The above example makes use of two local classes and these will have their own respective class file when compiled, as shown next.

$ tree build/classes/java

build/classes/java

└── main

└── demo

├── App$1Person.class

├── App$2Person.class

└── App.class

I do not like local classes and don’t recall any usage of these outside books. The reason I do not like them is that they are quite cryptic and make it hard to read the method. When needed, I use inner static classes, which gives the same benefit without polluting methods.

Note that local classes are inaccessible from outside the method. This means that we cannot test these classes outside the method.

JEP 360: Sealed Classes (Preview)

Java 15 will preview a new feature as defined by JEP 360: Sealed Classes (Preview).

What will sealed classes provide us? Say that our application has two types of coins, gold coins and silver coins and by design we cannot have other types of coins. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class Coin {

private Coin() {

}

public static class GoldCoin extends Coin {

}

public static class SilverCoin extends Coin {

}

}

Up to now, we can control our types using a combination of private constructors and inner static classes.

One of the downsides of the above approach is that the Coin class may become a bit bulky especially once we start pouring in logic. Java 15 will introduce a new concept of sealed classes, where the sealed class will define the classes that it permits to extend it, as shown next.

package demo;

public sealed class Coin

permits GoldCoin, SilverCoin {

}

The above example will not yet work as of now, Java 15 is still in early access. With the preview enabled, the Coin class only permits the GoldCoin and the SilverCoin to extend it. The GoldCoin class and the SilverCoin class can simply extend the sealed Coin class, as shown next.

The gold coin class

package demo; public class GoldCoin extends Coin { }The silver coin class

package demo; public class SilverCoin extends Coin { }

Note that this feature will be released in preview, and you will need to enable the preview mode while compiling and running the application.