Initialisation blocks

Table of contents

Static initialisation block

We use constructors to initialise the object’s properties. How can we initialise static fields? Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.Random;

public class App {

private static final int SECRET_NUMBER;

static {

final Random random = new Random();

SECRET_NUMBER = random.nextInt( 10 );

}

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

System.out.printf("The secret number is %d%n", SECRET_NUMBER);

}

}

The above example makes use of static initialisation block to initialise the SECRET_NUMBER to a random number. An instance of Random class is created and used to generate a random number. The instance of the Random is not available outside the static initialisation block and will be garbage collected at a later stage. The above will print.

The secret number is 7

The static initialisation blocks are not very commonly used and other approaches are usually preferred, such as the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.Random;

public class App {

private static final int SECRET_NUMBER = generateSecretNumber();

private static int generateSecretNumber() {

final Random random = new Random();

return random.nextInt( 10 );

}

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

System.out.printf( "The secret number is %d%n", SECRET_NUMBER );

}

}

Can we invoke a static initialisation block programmatically?

No. We cannot interact with the static initialisation block as we do with methods. The static initialisation block is invoked automatically by the Java runtime environment.

I tend to stay away from the static initialisation blocks and prefer the methods instead, unless required.

When and how many times is the static initialisation block invoked?

The static initialisation block is executed, once, when the class is loaded. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class ExecutionOrder {

static {

System.out.println( "Initialisation Block" );

}

private static final int STATIC_FIELD = initialiseStaticField();

private static int initialiseStaticField() {

System.out.println( "Initialise Static Field" );

return 7;

}

public static void printStaticField() {

System.out.printf( "The static constant field value is %d%n", STATIC_FIELD );

}

}

The above example contains an initialisation block and static field, which is initialised through a static method. Let’s consider several examples and see when the class is actually initialised.

Declaring a variable of type

ExecutionOrderwithout interacting with the class nor the varialble.package demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { ExecutionOrder a; System.out.println( "Done" ); } }The class is not used, thus will not be loaded. Therefore, the static initialisation block is not invoked.

DoneCreate a method that takes an

ExecutionOrderas a parameterpackage demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { doSomething( null ); System.out.println( "Done" ); } private static void doSomething( ExecutionOrder a ) { } }The class is not used, thus will not be loaded.

DoneInvoke the

printStaticField()method several timespackage demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { ExecutionOrder.printStaticField(); ExecutionOrder.printStaticField(); ExecutionOrder.printStaticField(); System.out.println( "Done" ); } }This time the class is used as the

printValue()method is invoked several time.Initialisation Block Initialise Static Field The static constant field value is 7 The static constant field value is 7 The static constant field value is 7 DoneNote that the static initialisation block is invoked first followed by the initialising the static fields. Both of these are invoked once, when the class is loaded.

Create instances of type

ExecutionOrderpackage demo; public class App { public static void main( final String[] args ) { new ExecutionOrder(); new ExecutionOrder(); new ExecutionOrder(); System.out.println( "Done" ); } }Same as before, the static initialisation block and the initialising the static fields are invoked once, when the class is loaded.

Initialisation Block Initialise Static Field Done

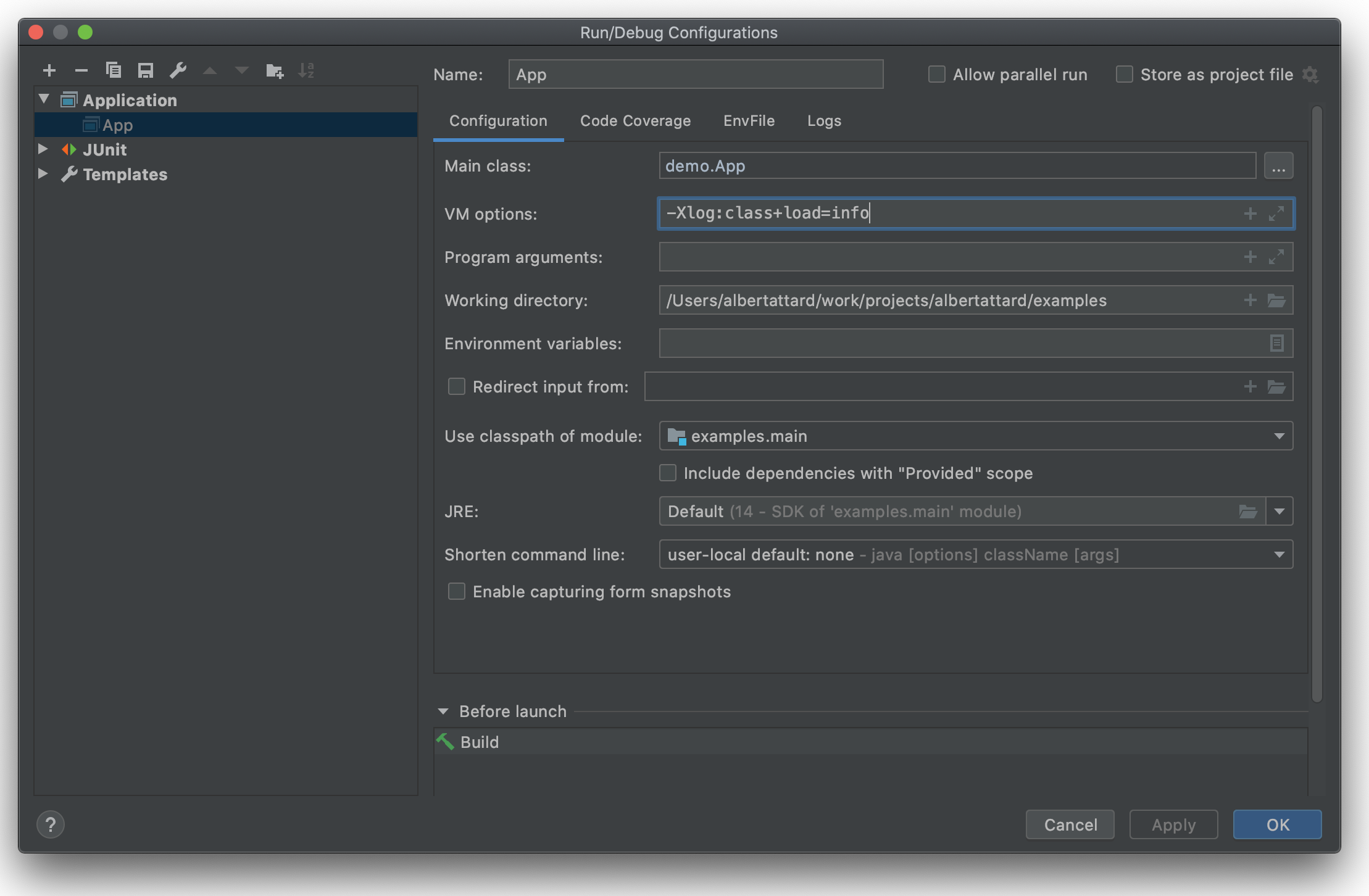

Alternatively, we can use the JVM flags, such as -Xlog:class+load=info, to see what classes are being loaded.

This will print all classes that are loaded by the classloader. You will be surprised by the number of classes loaded just to run a simple program. The following example truncates all classes, except ours.

...

[0.143s][info][class,load] demo.App source: file:out/production/classes/

[0.145s][info][class,load] demo.ExecutionOrder source: file:out/production/classes/

Initialisation Block

Initialise Static Field

...

The static constant field value is 7

Done

...

What happens if an exception is thrown from within the static initialisation block?

If an exception is thrown from within static initialisation block, an ExceptionInInitializerError is thrown in return. Note that this is not an Exception, but an Error.

Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class FaultyStaticInitialisationBlock {

static {

if ( true ) {

throw new RuntimeException( "Faulty static initialisation block" );

}

}

}

In the above example, we had to trick the compiler using an if statement. Without the if statement, the example will not compile. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

new FaultyStaticInitialisationBlock();

}

}

Running the above example will fail with ExceptionInInitializerError as shown next.

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ExceptionInInitializerError

at demo.App.main(App.java:6)

Caused by: java.lang.RuntimeException: Faulty static initialisation block

at demo.FaultyStaticInitialisationBlock.<clinit>(FaultyStaticInitialisationBlock.java:7)

... 1 more

Can we have more than one static initialisation block?

Yes. We can have many static initialisation block. The static initialisation blocks are executed in the order that they are defined. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class MultipleStaticInitialisationBlocks {

static {

System.out.println( "First static initialisation block" );

}

static {

System.out.println( "Second static initialisation block" );

}

}

The above class has two static initialisation blocks.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

new MultipleStaticInitialisationBlocks();

}

}

The initialisation blocks are executed in the order that they are defined.

First static initialisation block

Second static initialisation block

I tend to stay away from static initialisation block and prefer using methods instead. Note that multiple initialisation block may add to the confusion. Consider the following class.

package demo;

public class MultipleStaticInitialisationBlocks {

public static final int STATIC_FINAL_FIELD;

public static int STATIC_FIELD;

static {

STATIC_FINAL_FIELD = 7;

STATIC_FIELD = 3;

}

static {

STATIC_FIELD = 33;

}

}

The static field, STATIC_FIELD is set in both static initialisation block. The second block will overwrite the values set by the first block as shown next.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

System.out.println( MultipleStaticInitialisationBlocks.STATIC_FIELD );

}

}

The above program will print

33

Whenever I find myself asking “what will happen…”, I consider refactoring instead of testing it out.

Initialisation block

Java provides several ways to initialise properties within an object. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.Random;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final int secretNumber;

public Person( final String name ) {

this.name = name;

final Random random = new Random();

this.secretNumber = random.nextInt( 10 );

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, secretNumber=%d}", name, secretNumber );

}

}

The Person class has two properties, the name and a secretNumber. The name is provided to the constructor while the secretNumber is generated in the constructor.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Person a = new Person( "Jade" );

final Person b = new Person( "Aden" );

System.out.println( a );

System.out.println( b );

}

}

When creating new instances of the Person class we only pass the person’s name while the secret number is generated randomly.

Person{name=Jade, secretNumber=2}

Person{name=Aden, secretNumber=3}

There are other ways to initialise the secretNumber. One other option is to use initialise blocks as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.Random;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final int secretNumber;

{

final Random random = new Random();

secretNumber = random.nextInt( 10 );

}

public Person( final String name ) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, secretNumber=%d}", name, secretNumber );

}

}

This is not commonly used. Other alternatives, such as the one shown next, are more commonly used.

package demo;

import java.util.Random;

public class Person {

private final String name;

private final int secretNumber = createSecretNumber();

public Person( final String name ) {

this.name = name;

}

private static int createSecretNumber() {

final Random random = new Random();

return random.nextInt( 10 );

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format( "Person{name=%s, secretNumber=%d}", name, secretNumber );

}

}

When using methods to initialise fields, please make sure that these cannot be overridden as otherwise you may get into some surprises.

When is the initialisation block invoked?

The initialisation block is invoked before the properties are initialised but after the static initialisation block. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class ExecutionOrder {

static {

System.out.println( "Initialisation static block" );

}

{

System.out.println( "Initialisation block" );

}

private static final int STATIC_FIELD = initialiseStaticField();

private final int property = initialiseProperty();

public ExecutionOrder() {

System.out.println( "Constructor" );

}

private static int initialiseStaticField() {

System.out.println( "Initialise static field" );

return 7;

}

private static int initialiseProperty() {

System.out.println( "Initialise property" );

return 7;

}

public static void printStaticField() {

System.out.printf( "The static constant field value is %d%n", STATIC_FIELD );

}

}

The above example tracks all five initialisation points of a class, shown in the following table.

| # | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Static initialisation block |

| 2 | Static fields |

| 3 | Initialisation block (Instance) |

| 4 | Initialisation property |

| 5 | Constructor |

The initialisation points are invoked in the order shown in the above table as we will see in the following examples. Consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

ExecutionOrder.printStaticField();

System.out.println( "Done" );

}

}

Note that the above example is not creating a new instance of a class. None of the instance initialisers points are invoked.

Initialisation static block

Initialise static field

The static constant field value is 7

The follow table show how each initialisation point was invoked and in which order these were invoked.

| # | Name | Invoked |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Static initialisation block | Invoked first, once |

| 2 | Static fields | Invoked second, once |

| 3 | Initialisation block (Instance) | Not invoked |

| 4 | Initialisation property | Not invoked |

| 5 | Constructor | Not invoked |

Now consider the following example.

package demo;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

new ExecutionOrder();

new ExecutionOrder();

new ExecutionOrder();

System.out.println( "Done" );

}

}

This time we are creating three instances of the ExecutionOrder.

Initialisation static block

Initialise static field

Initialisation block

Initialise property

Constructor

Initialisation block

Initialise property

Constructor

Initialisation block

Initialise property

Constructor

Done

The follow table show how each initialisation point was invoked and in which order these were invoked.

| # | Name | Invoked |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Static initialisation block | Invoked first, once |

| 2 | Static fields | Invoked second, once |

| 3 | Initialisation block (Instance) | Invoked first (after static), every time an object is created |

| 4 | Initialisation property | Invoked second, every time an object is created |

| 5 | Constructor | Invoked last, every time an object is created |

What is double brace initialization?

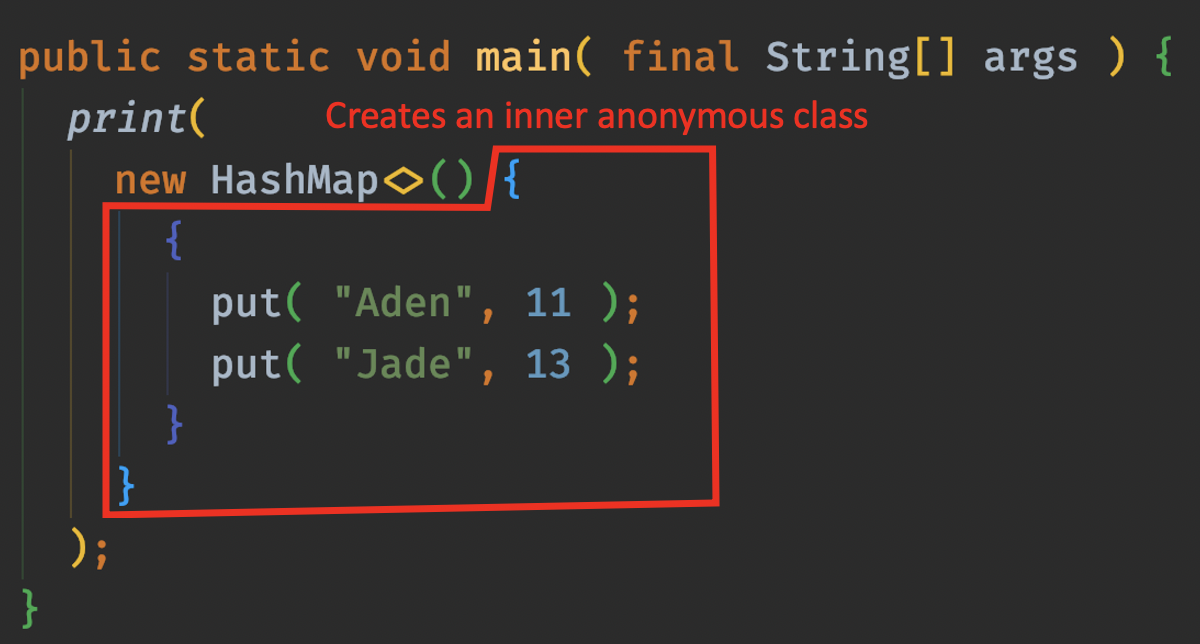

Double brace initialization takes advantage of inner anonymous classes and initialisation block to inline the creation and population of some types. Consider the following example.

package demo;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

final Map<String, Integer> ageByName = new HashMap<>();

ageByName.put( "Aden", 11 );

ageByName.put( "Jade", 13 );

print( ageByName );

}

private static void print( final Map<String, Integer> map ) {

map.forEach( ( name, age ) -> System.out.printf( "%s is %d years old%n", name, age ) );

}

}

The above example creates a map that contains persons’ names and their respective age and then passes this map to a method to be printed. Without worry about the syntax used in this example, note that here we created an instance of HashMap, populate it with values and then pass this variable to the method.

We can “simplify” this by creating the map, populate it and pass it to the method on the fly, without saving it to a variable, as shown next.

package demo;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class App {

public static void main( final String[] args ) {

print( new HashMap<>() { {

put( "Aden", 11 );

put( "Jade", 13 );

} } );

}

private static void print( final Map<String, Integer> map ) { /* ... */ }

}

I am not fond of this pattern, and it is more popular than you may think. I don’t like it as it is a bit cryptic to read and understand, and I consider that as a code smell.

Let’s break this further.

Reformat the code to separate the curly brackets

print( new HashMap<>() { { put( "Aden", 11 ); put( "Jade", 13 ); } } );Here we are creating an inner class as shown next

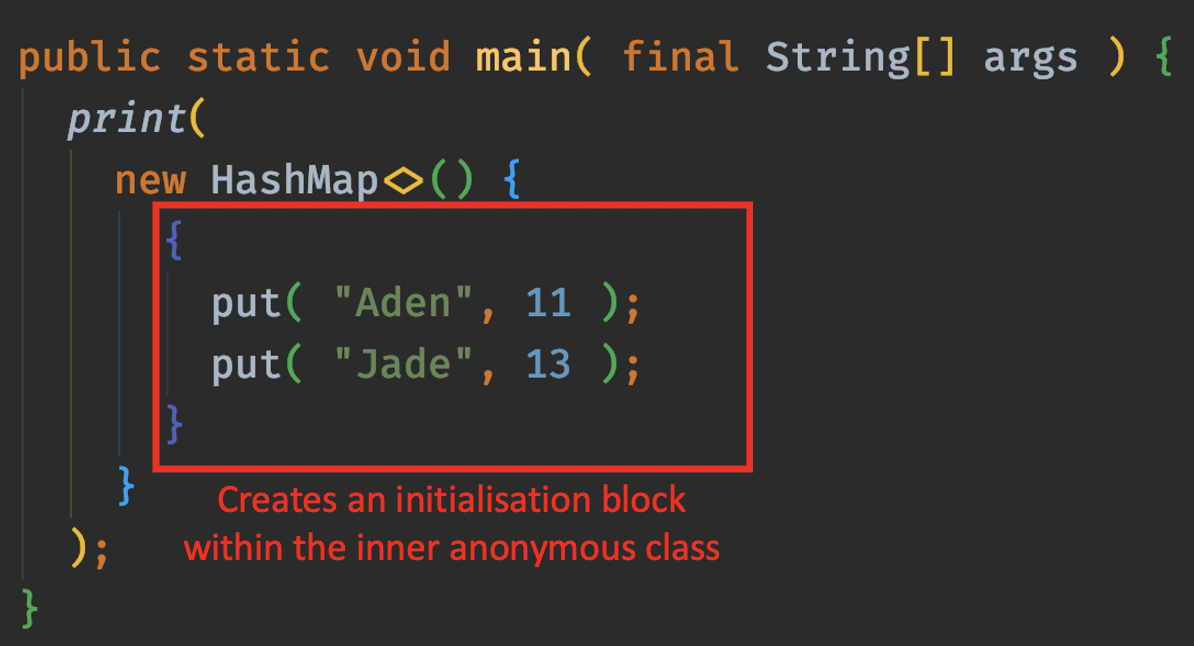

Then we take advantage of the initialisation block to add our items

The initialisation block is invoked before the properties are initialised and the constructor is called. How come this works? The class must be in an invalid state?

Note that the anonymous inner class, is a class that extends another class. The parent class, the HashMap in our case, is initialised before the subtypes, our anonymous inner class, and that’s why this works. The map is properly setup before our initialisation block is invoked.

With that said, note how long we had to go to discuss this. I prefer to use methods instead to create my objects. Recent versions of Java, such as Map.of(), made this approach obsolete in some cases as shown next.

print( Map.of( "Aden", 11, "Jade", 13 ) );